In mijn vorige column schreef ik hoe de Medische krijgsheren onder bescherming van de Assyrische koning steeds machtiger werden. Een krijgsheer die door de Assyrische koning werd erkend kon op diens steun rekenen wanneer zijn gezag van onderop werd betwist. Hierdoor kreeg het ‘ambt’ van stamhoofd een meer permanent karakter. Bovendien leidde de Assyrische kolonisatie tot een toename van de handel langs de Khorasan-route. De Medische krijgsheren verrijkten zich en lieten heuvelforten, heiligdommen en zuilenhallen bouwen.

Het einde van de Assyrische overheersing

Uitgaande van deze situatie kan men zich goed voorstellen dat het einde van de Assyrische overheersing verstrekkende gevolgen moet hebben gehad voor de Meden. Welke gevolgen dat precies waren is moeilijk te achterhalen. De Assyrische bronnen maken na 656 v. Chr. geen melding meer van de Meden en in het archeologisch bestand is te zien dat veel heuvelforten in deze periode worden verlaten. Waar eerst krijgsheren met hun entourage vertoefden, nemen nu herders met hun vee hun intrek. Om te achterhalen welke ontwikkelingen zich in de Duistere Periode tussen 670 en 550 v. Chr. hebben voltrokken zijn we aangewezen op een klein aantal Babylonische en Hebreeuwse bronnen en Griekse auteurs als Herodotus, die veel later schreven. Het idee dat de Meden in deze Duistere Periode een wereldrijk hebben gesticht is vooral gebaseerd op het werk van Herodotus.

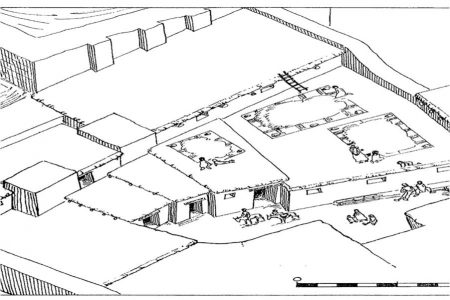

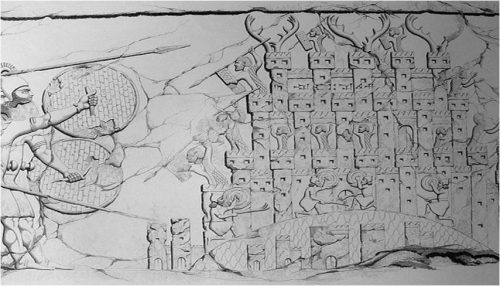

Reeds rond 700 v. Chr. werd het (waarschijnlijk) Ellipiaanse fort Baba-Jan verlaten, waarop (waarschijnlijk) Medische herders er hun intrek namen. Hierboven een reconstructie van Baba-Jan met de door herders aangebrachte veestallen op de binnenplaats.

Het Medische Rijk volgens Herodotus

Volgens Herodotus (1.95-1.106) waren de Meden het eerste volk dat zich losmaakte van de Assyrische overheersing. Kort daarna vervallen ze echter tot anarchie. Uiteindelijk slaagt een rechter genaamd Deioces erin zes Medische stammen onder zijn gezag te verenigen. Zijn zoon Fraortes verovert naburige koninkrijken, waaronder Perzië, en valt Assyrië binnen. Fraortes sneuvelt echter tijdens deze invasie, waarop de Scythen, die Assyrië te hulp waren gekomen, de macht overnemen in Medië. De leider van de Scythen is Madyes, zoon van Protothyes (de Bartatua die een bondgenootschap sloot met de Assyrische koning Esarhaddon). Uiteindelijk slaagt Fraortes’ zoon Cyaxares erin de Scythen te verdrijven, het Medische Rijk te herstellen en Assyrië te veroveren.

Het Medische Rijk volgens contemporaine bronnen

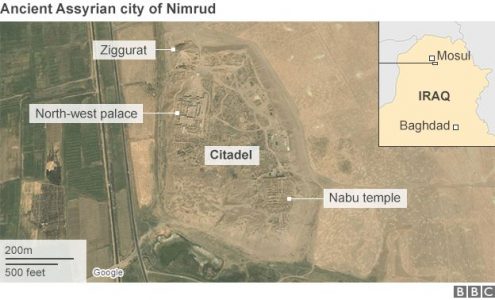

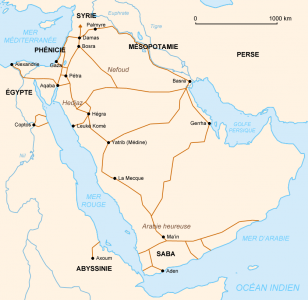

Dat Cyaxares een rol heeft gespeeld in de ondergang van Assyrië wordt bevestigd door Babylonische kronieken. Cyaxares zou in 614 v. Chr. de heilige stad Ashur hebben veroverd en vervolgens een bondgenootschap hebben gesloten met de Babylonische koning Nabopolassar. In 612 v. Chr. nemen de twee koningen samen de Assyrische hoofdstad Nineveh in. Na de val van Nineveh lijken de relaties tussen de Babyloniërs en de Meden te zijn bekoeld. In 593 v. Chr. voorspelt de profeet Jeremia dat de Meden Babylonië zouden binnenvallen. Hij beschrijft een coalitie van Urarteeërs, Manneeërs, Scythen en meerdere Medische koningen. Niet lang daarna – tussen 590 en 585 v. Chr. – zou Cyaxares volgens Herodotus (1.73-74) oorlog hebben gevoerd tegen het koninkrijk Lydië, in westelijk Anatolië. De Meden bleven dus in staat grote veldtochten naar verre gebieden te organiseren.

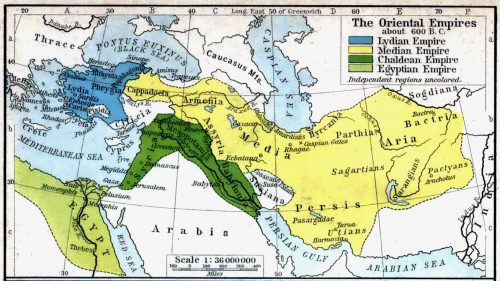

De belangrijkste grootmachten in het Nabije Oosten rond 550 v. Chr. In navolging van Herodotus is het Medische Rijk hier behoorlijk groot afgebeeld. Naar: Shepherd, W.R. (1923): ‘The Historical Atlas’.

Medië als stammencoalitie

Op basis van Herodotus’ verslag is men er lange tijd vanuit gegaan dat de Meden een wereldrijk hadden gevormd dat grote delen van Iran en oostelijk Anatolië omvatte. Voor het bestaan zo’n groot rijk is echter noch in het archeologische bestand, noch in de contemporaine bronnen hard bewijs gevonden. De Nederlandse historica Heleen Sancisi-Weerdenburg (1944-2000) trok het idee van een Medisch Rijk dan ook in twijfel. Volgens haar is er geen bewijs voor het bestaan van een staatssamenleving in Iran tijdens de zogenaamde Duistere Periode. De regio zou zelfs in politiek en economisch verval geweest zijn. Als alternatief stelde Sancisi-Weerdenburg voor dat het Medische Rijk meer weg had van een stammencoalitie.

Wat is een stammencoalitie?

Een stammencoalitie komt tot stand wanneer leiders van verschillende stammen besluiten samen te werken. Vaak kiezen zij één capabele krijgsheer uit om de coalitie te leiden. Wanneer veel stammen zich bij zo’n coalitie aansluiten kan deze in korte tijd enorm groot worden en ook enorm veel schade aanrichten. De machtsverhoudingen binnen zo’n stammencoalitie zijn echter wel instabiel. Macht is niet geïnstitutionaliseerd, maar is gebaseerd op het persoonlijke charisma van de leider. Wanneer de leiders van de stammen massaal besluiten zich uit de stammencoalitie terug te trekken, of wanneer één krijgsheer de leider van de stammencoalitie naar de kroon steekt, kan zo’n stammencoalitie zo weer uiteenvallen.

Turkse en Mongoolse volken kwamen op zogenaamde Kurultai’s bijeen om de leiders van hun stammencoalities te kiezen. De Medische stammencoalitie kan ook op een dergelijke manier tot stand zijn gekomen. Bron: http://kazakhworld.com/election-khan-kurultai-kazakhkhanate/#prettyPhoto

De Duistere Periode

Laat ons nu zien hoe we de gebeurtenissen in de Duistere Periode in het licht van deze hypothese kunnen interpreteren. De Duistere Periode lijkt te zijn begonnen nadat de Assyriërs rond 670 v. Chr. hun grip op het Zagrosgebergte waren kwijtgeraakt. Hierdoor werden de Medische krijgsheren niet langer beschermd door de Assyrische koning en stortte ook de handel langs de Khorasan-route in. Tot overmaat van ramp werden de Medische stammen getergd door Cimmerische en Scythische rooftochten. Veel Medische koninkrijkjes zijn waarschijnlijk in de loop van de zevende eeuw v. Chr. ten onder gegaan. De koninkrijkjes van pre-Indo-Europese volken als de Manneeërs, Elippianen en Kassieten gingen eveneens ten onder, waardoor de Meden zich eenvoudiger op hun territorium konden vestigen.

De opkomst van Cyaxares

Met de ineenstorting van de traditionele machtsstructuren kwam er ruimte voor nieuwe machthebbers. De eerdergenoemde Cyaxares lijkt er als eerste in te zijn geslaagd de Medische stammen te verenigen. Mogelijk is deze stammencoalitie tot stand gekomen in een poging de Scythen (eveneens een stammencoalitie) te verslaan, zoals Herodotus suggereert. Door zijn overwinning op de Scythen kwam Cyaxares bekend te staan als een groot krijgsheer, waardoor hij later ook werd uitgekozen om de expedities tegen Assyrië en Lydië te leiden.

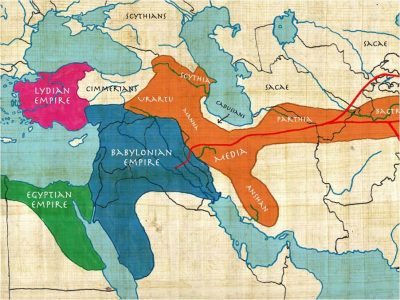

De belangrijkste grootmachten in het Nabije Oosten rond 550 v. Chr. (eigen werk). De omvang van het Medische Rijk is hier aangepast aan moderne inzichten.

De stammencoalitie groeit

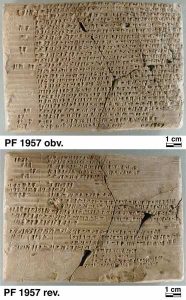

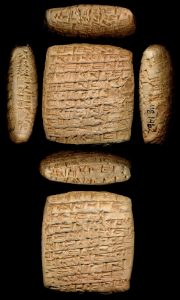

Na zijn indrukwekkende veldtochten tegen het eens zo gevreesde Assyrië nam Cyaxares’ invloed over naburige volken toe. Als we Jeremia mogen geloven sloten ook Urartu, Mannea en de Scythen zich aan bij zijn coalitie. Toch was er geen sprake van een gecentraliseerd wereldrijk. Zo heeft Jeremia het over ‘de koningen der Meden’ (de meervoudsvorm in de oorspronkelijke Hebreeuwse tekst is in de meeste vertalingen bij wijze van hypercorrectie genegeerd), wat impliceert dat de Meden nog altijd meerdere leiders hadden. Bovendien noemt Jeremia Urartu, Mannea en de Scythen als aparte mogendheden. Weliswaar bondgenoten, maar geen onderdanen van de Meden. De auteur van de Nabonidus Cylinder heeft het over “vele koningen die aan hun (i.e. van de Meden) zijde marcheren”.

De Perzische overname

Aan het begin van de zesde eeuw v. Chr. bestond er dus een Medische stammencoalitie die grote delen van noordelijk en westelijk Iran besloeg. De leider van deze stammencoalitie – Cyaxares – stond bovendien aan het hoofd van een bondgenootschap waartoe ook voorheen machtige koninkrijken als Urartu, Mannaea en Scythië behoorden. Dit bondgenootschap streed tegen Lydië en leefde op gespannen voet met het Babylonische Rijk. Dat dit bondgenootschap door latere auteurs voor een wereldrijk is aangezien is goed te begrijpen. De vraag die ons nu rest is: Hoe is dit Medische Rijk Perzisch geworden? Daarover schrijf ik in mijn volgende column.

![Plattegrond van een Parthische tempel in Ashur. Door Udimu (naar: Colledge, The Parthians, 126, fig. 32 (c)) [GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html), CC-BY-SA-3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/) or CC BY 2.5 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.5)], via Wikimedia Commons.](http://sargasso.nl/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/Assur_temple-231x300.jpg)