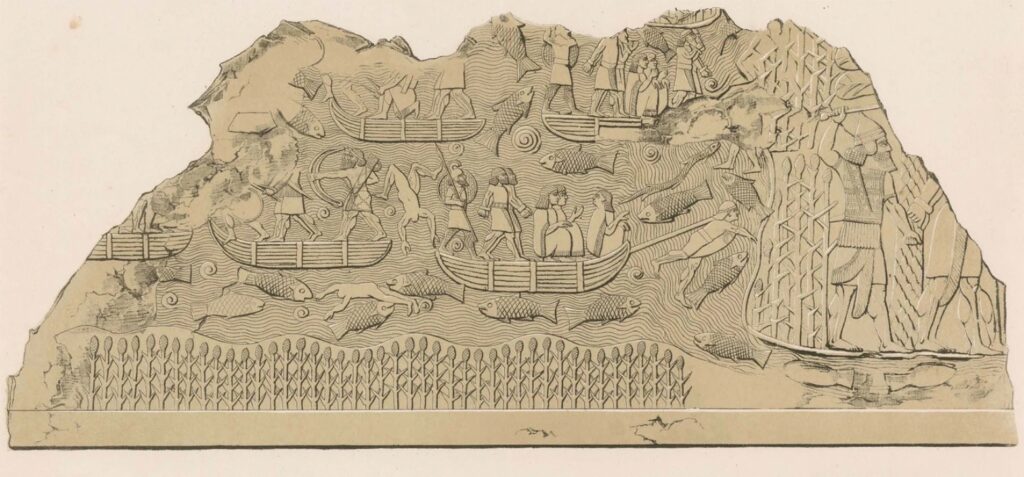

Dosseman, CC BY-SA 4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

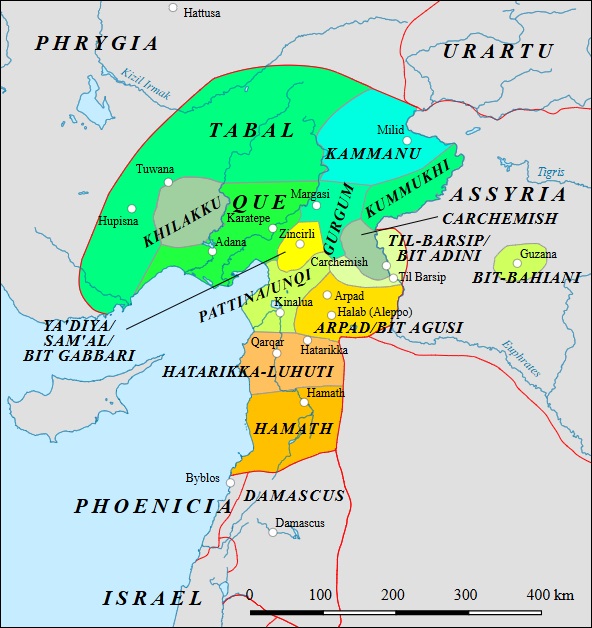

If you had travelled through northern Mesopotamia in the tenth century BCE, one thing would have stood out immediately: there was no central authority. The region was a political mosaic of small kingdoms, tribal confederations, and local strongmen controlling scattered territories along rivers and steppe margins. None was strong enough to dominate the others for long.

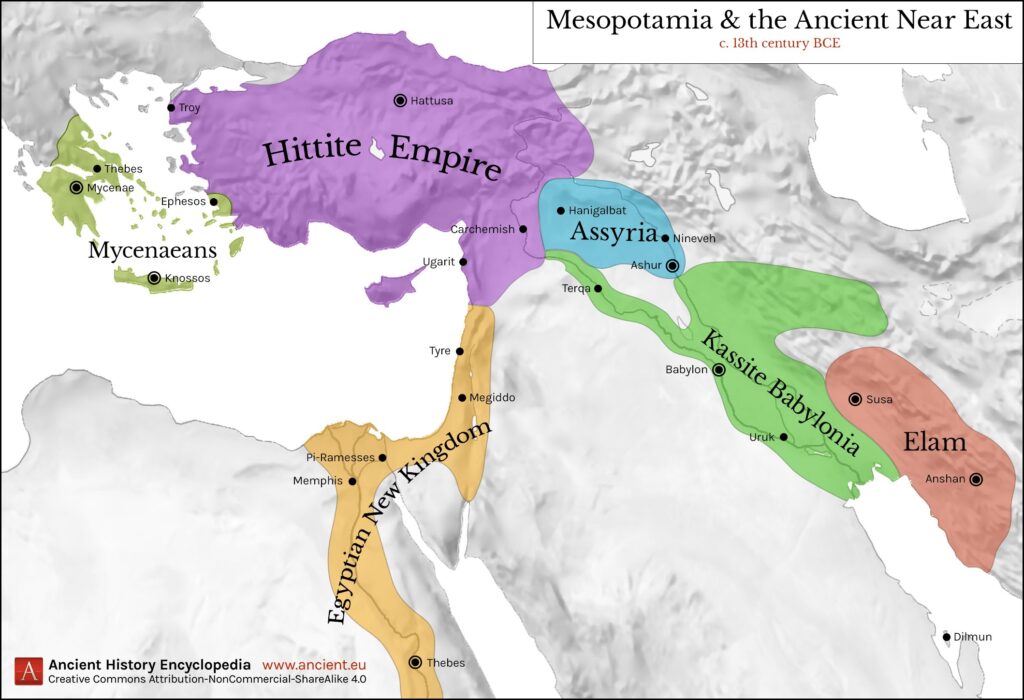

This fragmented landscape emerged in the aftermath of the Late Bronze Age collapse. Until the reign of Tiglath-Pileser I (r. 1114–1076 BCE), these lands had belonged to the Middle Assyrian kingdom. After his death, however, the structures that had once held northern Mesopotamia together gradually unraveled. Fortresses and farming settlements were abandoned, long-distance trade routes became less secure, and Aramaean tribal groups spread across much of the countryside.

In this environment, power rested largely on kinship and local loyalties. Instead of large territorial states, the region was dominated by smaller dynastic polities centred on ruling families and their followers. One of these was Bīt-Baḫiāni, an Aramaean kingdom along the Ḫābūr River whose capital was Guzana (modern Tell Halaf).

Continue reading “Bīt-Baḫiāni, the kingdom that thrived by aligning with Assyria”