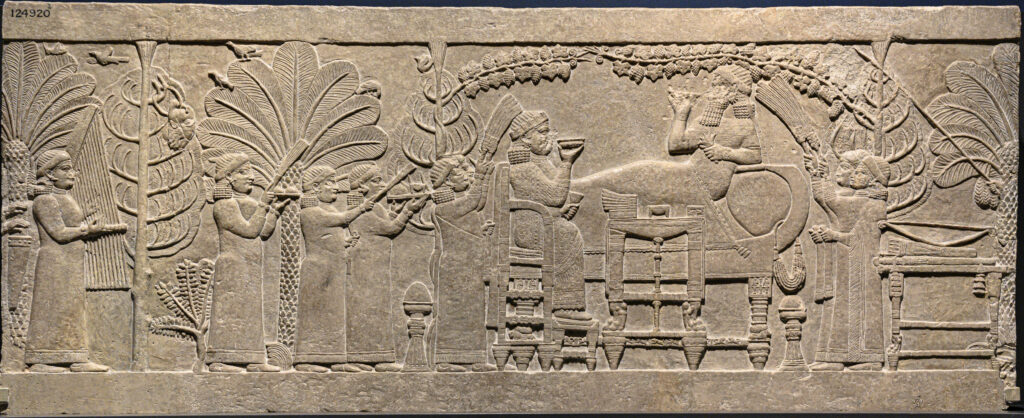

Allan Gluck, CC BY 4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

In the previous installments of this series, we saw how Urartu failed to restrain Assyria from the outside and how Babylonia — older, richer, and more prestigious — challenged it from within. In this episode, we turn eastward to a very different kind of rival. For over a century, Elam repeatedly intervened in Mesopotamian affairs, shaping the political order of the Near East. Yet unlike Assyria, it never sought to build an empire of its own.

In Mesopotamian sources, Elam often appears as a familiar villain: ruled by treacherous kings, threatening Mesopotamian kingdoms with sudden raids and inconvenient interventions. But this image obscures a deeper reality. Elam was not a marginal spoiler, but one of the oldest and most enduring great powers of the ancient Near East, with its own imperial traditions, strategic culture, and long experience in managing Mesopotamian politics. If Elam never produced balance, it was not because it lacked power. It was because it never sought hegemony — only security.

A tradition of meddling

Elam’s involvement in Mesopotamian politics long predated Assyria’s rise. From the third millennium BCE onward, Elamite rulers intervened repeatedly west of the Zagros. Elamite armies entered Sumer and Akkad, installed client kings, and carried off divine statues to Susa. At various moments, Elam dominated large parts of southern Mesopotamia outright.

In the twelfth century BCE, kings such as Šutruk-Nahhunte I and Kutir-Nahhunte II famously conquered Babylon, removed the stele of Hammurabi, and proclaimed Elamite supremacy. These were not peripheral raids. They were acts of imperial power.

This history shaped Elam’s strategic outlook. Elam was both a frontier state and a regional empire. Its security depended on developments in Mesopotamia. A strong, unified power west of the Zagros was always a potential threat. A fragmented Mesopotamia was safer and more manageable.

By the time Assyria emerged as the dominant northern power, Elam already possessed centuries of experience in manipulating Mesopotamian politics.

Stability without expansion

In the early Iron Age, Elam entered a period of relative stability. From roughly the late ninth to the mid-eighth century BCE, Elamite kings focused primarily on consolidating control over the Susiana plain and the Zagros foothills. Unlike Assyria, Elam did not pursue systematic territorial expansion. Its campaigns were limited, its administration conservative. The court at Susa concentrated on maintaining internal cohesion and defending its western frontier.

Initially, Elam showed little interest in confronting Assyria directly. Distance and geography provided a buffer, and Babylonia still functioned as a political intermediary. As long as southern Mesopotamia remained unstable, Elam’s strategic position was tolerable. This equilibrium ended when Assyria began to impose sustained control over Babylonia.

Elam and the Babylonian question

From the late eighth century BCE onward, Elam’s interventions became increasingly focused on a single objective: preventing Assyria from transforming Babylonia into a secure imperial province.

When Merodach-Baladan II ruled an independent Babylonia (722–710 BCE), he found a natural ally in Elam. Under kings such as Humban-nikaš I (r. 743–717) and Šutruk-Nahhunte II(r. 717-699 BCE), Elam provided diplomatic backing and military assistance. Babylon functioned as a buffer state, separating Elam from the Assyrian frontier.

The same pattern repeated under Mušezib-Marduk (r. 693–689 BCE). Elamite forces under Hallušu-Inšušinak (r. 699–693 BCE) and Humban-numena III (r. 692–688) fought alongside Babylonian armies against Sennacherib. In 691 BCE, the coalition confronted Assyria at the battle of Halule, one of the largest engagements of the period.

Elam’s objective remained consistent. It did not seek to annex Babylonia. It sought to keep it autonomous and hostile to Assyria. This was strategic containment.

Cooperation and Conflict

Elam’s policy produced an unstable oscillation between hostility and accommodation. When Assyria exercised firm control over Babylonia, relations between the two empires improved. Under Esarhaddon (r. 681–669 BCE), diplomacy resumed and open warfare subsided. When famine struck Elam in the early 660s, King Urtak even received grain from Assyria, and Elamite refugees were sheltered in Assyrian territory. For several years, relations remained peaceful.

This fragile equilibrium collapsed through internal Elamite politics. Around 664 BCE, Urtak was persuaded by Babylonian and Aramaean figures to attack Babylonia. Ashurbanipal repelled the incursion and Urtak soon died. His successor Teumman, who had seized the throne by force, attempted to eliminate rival branches of the royal family. Dozens of princes fled to the Assyrian court. When Teumman demanded their extradition, Ashurbanipal refused.

War followed. In 653 BCE, Assyrian and Elamite armies met at the river Ulai, where Teumman was defeated and killed. Ashurbanipal installed a friendly ruler on the Elamite throne, restoring temporary stability. But Elam’s internal instability and Assyrian intervention poisoned relations permanently. When the Babylonian revolt of Šamaš-šumu-ukin broke out (652–648 BCE), Elam again became the principal external supporter of anti-Assyrian resistance. Elamite troops, resources, and political backing sustained the anti-Assyrian coalition for years. For Ashurbanipal, this was no longer tolerable.

Devastation without domination

In the aftermath of the rebellion, Ashurbanipal launched a sequence of brutal campaigns against Elam between c. 647 and 639 BCE. Assyrian inscriptions describe the sack of major cities, the destruction of temples, the capture of royal tombs, and the humiliation of Elamite kings. Susa itself was plundered. The rhetoric is annihilatory.

Yet the very repetition of these campaigns reveals their limitation. Assyria inflicted enormous damage, but it did not annex Elam. There was no lasting occupation, no provincial system, no durable incorporation into the Assyrian imperial framework. The terrain, the distance, and Elam’s internal resilience imposed hard limits on Assyrian power. Elam was shattered but not absorbed.

What Elam reveals about the failure of balance

Elam occupies a distinctive place among Assyria’s rivals. Unlike Urartu, it did not threaten the Assyrian heartland. Unlike Babylonia, it did not undermine Assyria from within. And unlike Egypt, it did not seek to reclaim lost imperial spheres.

Elam’s strategy was defensive and conservative. It aimed to constrain Assyria rather than to dominate Mesopotamia. In another system, such behavior might have formed the basis of a balance of power. In the Iron Age Near East, it did not. Elam acted alone. It lacked partners capable of sustained coordination. And once Assyria secured firm control over Babylonia, Elam was effectively bypassed: no longer central to the political order, no longer able to shape events decisively.

By the time Assyria collapsed, Elam had already been marginalized. And yet Elam did not vanish from history. Large parts of its territory, population, and administrative traditions would soon form the core of a new power rising east of Mesopotamia: Persia. When Cyrus the Great conquered Babylon in 539 BCE, he did so from lands that had once belonged to Elam.

In that sense, Elam represents one of the ironies of this story. It failed to restrain Assyria. It failed to balance the Iron Age system. But out of its ruins would emerge the empire that finally solved the problem Assyria never could: how to rule the Near East without destroying it.

In the next installment, we will turn to a far more fragile rival: Phrygia, a regional power whose rise and sudden disappearance show how external shocks could eliminate potential counterweights before they ever had a chance to matter.