When I look back on my university days at VU Amsterdam, one of the figures who left a lasting impression on me was my professor Bert van der Spek. Anyone who studied the Ancient Near East under him will recall his unshakable conviction that Hellenistic Babylonia — so often treated as a footnote between Alexander the Great and the Parthian Empire — was an extraordinary period in its own right. As students, we regularly heard about the massive project he was working on: the edition of the Hellenistic chronographic texts from Babylonia, those fragmentary but invaluable cuneiform accounts that offer a uniquely Babylonian view of the Seleucid and early Parthian world.

At the time, however, this enthusiasm did not quite reach me. I was more interested in what I thought of as “real” Mesopotamia: the world of Hammurabi, Ashurbanipal, Nebuchadnezzar II. The world before Hellenism complicated matters, before the “purity” of ancient Mesopotamia was — so I believed — “polluted” with imported Greekness. I was frustrated with classicists who ignored Near East influences of Graeco-Roman civilization, but ironically blind to the richness of the very period that brought these worlds even closer together. It has taken me a decade and a great deal of reading to realize just how naïve this was. The Hellenistic period in Babylonia was anything but a watered-down afterthought. It was a moment of profound cultural transformation. And now, with the publication of Babylonian Chronographic Texts from the Hellenistic Period, the results of many decades of work have finally seen the light of day. Tomorrow, Van der Spek will present his work at the Rijksmuseum van Oudheden.

Caught between continuity and change

What makes this period so interesting is the tension between ancient continuity and sudden change. By the third and second centuries BCE, cuneiform culture was already thousands of years old. Akkadian, the language of the scribes, had been used for everything from mathematical tables to royal propaganda to astrology. Yet by the Hellenistic era, it survived only in the hands of a narrow priestly and scholarly elite centered in temples like the Esagila in Babylon or the Eanna in Uruk. The everyday linguistic landscape of Mesopotamia had long since shifted toward Aramaic, while Greek elite culture — theaters, gymnasia, architecture — spread rapidly across the Near East.

This was not simply a matter of Greek culture replacing local culture. Rather, Babylonian intellectuals found themselves confronting a very different civilizational model, one that forced them to redefine what it meant to inherit a tradition that claimed uninterrupted continuity from the third millennium BCE.

Greek citizens in Babylon

The chronographic texts reveal how deeply the encounter between Macedonian rule and Babylonian tradition reshaped the city. One striking example is the Politai Chronicle (BCHP 13), a small tablet dated to 172/171 BCE, during the reign of Antiochus IV Epiphanes. This chronicle contains the earliest explicit reference to the puliṭe — the Babylonian rendering of politai — Greek or Hellenized citizens living in Babylon.

Until now, these politai were known almost exclusively from passing mentions in the Astronomical Diaries, where they typically appear in connection with administrative or judicial events, often alongside the governor, and are described as “annointing themselves with oil” for wrestling. It is striking that of all the characteristics of Greek culture, this one stood out for the Babylonians. The Politai Chronicle confirms, far more explicitly, that by the early 170s BCE Babylon contained a fully formed Greek civic group, not merely scattered settlers or soldiers.

What makes this chronicle so illuminating is the context in which the politai appear. Their recorded activities take place near the Great Gate of Babylon — the ceremonial, administrative, and ritual heart of the city. This is not a marginal settlement on the edge of the metropolis but a Greek-style civic body integrated into the city’s sacred topography. Their involvement in building activities near such an important location suggests institutional authority, communal organization, and even political recognition.

Seen in this light, the Politai Chronicle documents not just a demographic presence but a structural transformation: Babylon, the city of Hammurabi and Nebuchadnezzar II, was adapting its urban and institutional landscape to incorporate a Greek-style citizen body. For a city with such a deep sense of its own historical identity, this represents a remarkable chapter in its long story of reinvention.

Restoring a ruined temple

Another text, equally revealing in a different way, is the Ruin of Esagila Chronicle (BCHP 6). This tablet sheds light on the early Hellenistic attempts to restore the Esagila, the great temple complex of Marduk, and its adjacent ziggurat, Etemenanki: once the architectural symbol of Babylonian religious and political authority.

Unlike the polished and self-confident royal inscriptions, the Ruin of Esagila Chronicle offers a raw, unvarnished snapshot of events. It describes how the Seleucid crown prince — almost certainly Antiochus I, son of Seleucus I Nicator — visited the ruined site, performed sacrifices and offerings, and supervised debris removal with the help of soldiers, wagons, and even elephants. The image is both impressive and precarious: while trying to fulfill the traditional royal duty of temple restoration, the prince fell during a sacrifice on the ruined platform.

The reverse of the chronicle becomes even more intriguing. It reads like a record of a dispute or judicial hearing, involving accusations about laborers who failed to perform their tasks properly — perhaps even acts of sabotage. Here, instead of the triumphant voice of kings boasting about their piety, we see the administrative and political difficulties that accompanied such projects: shortages of skilled labor, mismanagement, competing interests, and the fragile balance between royal authority and local expectations.

The Ruin of Esagila Chronicle matters because it exposes the tension between royal ideology and practical reality. While Seleucid kings presented themselves as dutiful heirs of ancient Mesopotamian rulership, this chronicle shows what actually happened on the ground: rituals gone awry, accidents, worksite conflicts, and a crown prince struggling to impose order on a monumental project whose symbolic weight far exceeded its material stability. It is a glimpse behind the façade of empire.

When Egypt invaded Mesopotamia

A third chronicle dramatically reconfigures our understanding of Hellenistic geopolitics. The Invasion of Ptolemy III Chronicle (BCHP 11) offers Babylonian testimony about what appears to be the campaign of Ptolemy III Euergetes during the Third Syrian War (246–241 BCE).

Classical sources credit Ptolemy with boldly pushing eastward, farther than any Ptolemaic ruler before or after. But historians have long suspected exaggeration, given the logistical difficulties of extending Egyptian power into Mesopotamia. The Babylonian chronicles, however, tell a different story. The Invasion of Ptolemy III Chronicle describes troop movements, political upheavals, and local reactions that align with the presence of a Ptolemaic force deep inside the region.

What makes this chronicle so valuable is its perspective. Unlike Greek historians, the Babylonian scribes had no ideological reason to amplify Ptolemaic achievements. If anything, they tended to view all foreign dynasties with equal skepticism. Their neutral, matter-of-fact reporting therefore provides rare confirmation that Ptolemy III’s intervention was not a tale of courtly propaganda but a historical reality that disrupted Babylonian life.

This forces us to rethink the geopolitical landscape of the mid-third century BCE. Mesopotamia, far from being securely in Seleucid hands, was vulnerable to ambitious rivals capable of exploiting moments of instability. The chronicles thus attest to a far more fluid and contested Hellenistic world than the tidy maps in textbooks tend to suggest.

The Babylonian eye on the heavens

All of this stands alongside the better-known Astronomical Diaries, which form a major part of the new book and are now fully integrated into it. These diaries are among the most remarkable scientific records to survive from antiquity: daily or near-daily notes kept by Babylonian scholar-priests over the course of almost three centuries. They record the movement of the planets with astonishing regularity: the visibility, brightness, and anomalies of the moon, eclipses, conjunctions, and atmospheric phenomena, as well as weather, river levels, market prices, and political events.

What makes the diaries so interesting is not merely their quantity, but their intellectual ambition. They reveal a worldview in which the celestial and the terrestrial were fundamentally intertwined. For the Babylonian astronomers, it was not strange to note in the same breath that Jupiter stood in opposition, that the price of barley rose, that a thunderstorm struck the city, or that a foreign army appeared on the horizon. These events were not separate categories but elements of a single, observant way of reading the world. A world in which the gods communicated through both the sky and the marketplace. The diaries show us how carefully, methodically, and patiently the Babylonian scholars observed their environment, convinced that patterns could be detected and that meaning could be drawn from them.

The integration of the Astronomical Diaries into this new volume is significant because the diaries and the chronographic texts illuminate each other. The diaries provide the raw data: the daily accumulation of facts, observations, prices, omens, and disruptions. The chronicles, by contrast, provide the interpretation: they condense, summarize, and evaluate political events, creating a historical narrative out of the continuous flow of daily observations.

Having both together — for the first time in a single, coherent publication — allows us to see the Hellenistic Near East through Babylonian eyes with an unprecedented clarity. We can now trace how an eclipse noted in a diary might echo in a chronicle’s brief statement about royal anxiety, or how a spike in grain prices appears alongside a chronicle’s reference to unrest in the city. The diaries and the chronicles, read side by side, reveal the rhythms, crises, and daily realities of Babylonian life in a period of profound political change, and they show us the remarkable persistence of a millennia-old scholarly tradition that continued to make sense of the world even as empires rose and fell around it.

A new window into the late cuneiform world

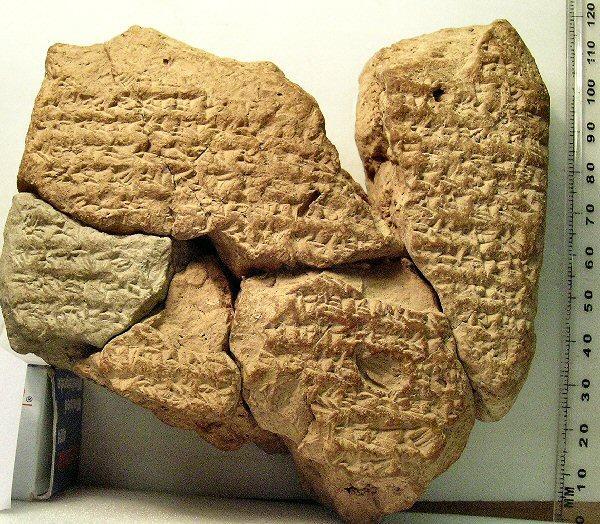

This is the world that Babylonian Chronographic Texts from the Hellenistic Period finally makes available in full. For the first time, all the relevant material — including previously unpublished tablets, the complete corpus of Hellenistic chronicles, the historical sections of the Astronomical Diaries, the Babylonian and Uruk King Lists, and a new edition of the Antiochus Cylinder — has been brought together in a single, coherent volume. The book provides new descriptions, transliterations, translations, and extensive commentary, along with an appendix explaining political institutions, temples, titles, and Graeco-Babylonian terminology. It is the first fully comprehensive edition of Babylonian historiography from the Hellenistic period, and it allows scholars to read these texts side by side as a unified corpus rather than scattered fragments.

An invitation to explore this world

For anyone who wants to understand how ancient cultures adapt under foreign rule, or how the last great cuneiform intellectual tradition continued to reinvent itself in the face of profound change, this book is essential reading. And if you would like to hear more about the work behind it, Bert van der Spek will present the volume tomorrow, Thursday 4 December 2025, at the Rijksmuseum van Oudheden in Leiden. Given how long this project has been in the making, I cannot imagine a more fitting moment to celebrate it.

Whether you attend the presentation or read the book yourself, I wholeheartedly recommend taking the opportunity. The world of Hellenistic Babylonia may seem like the twilight of an ancient civilization, but through these texts it becomes clear that it was also a world of extraordinary resilience, creativity, and insight.