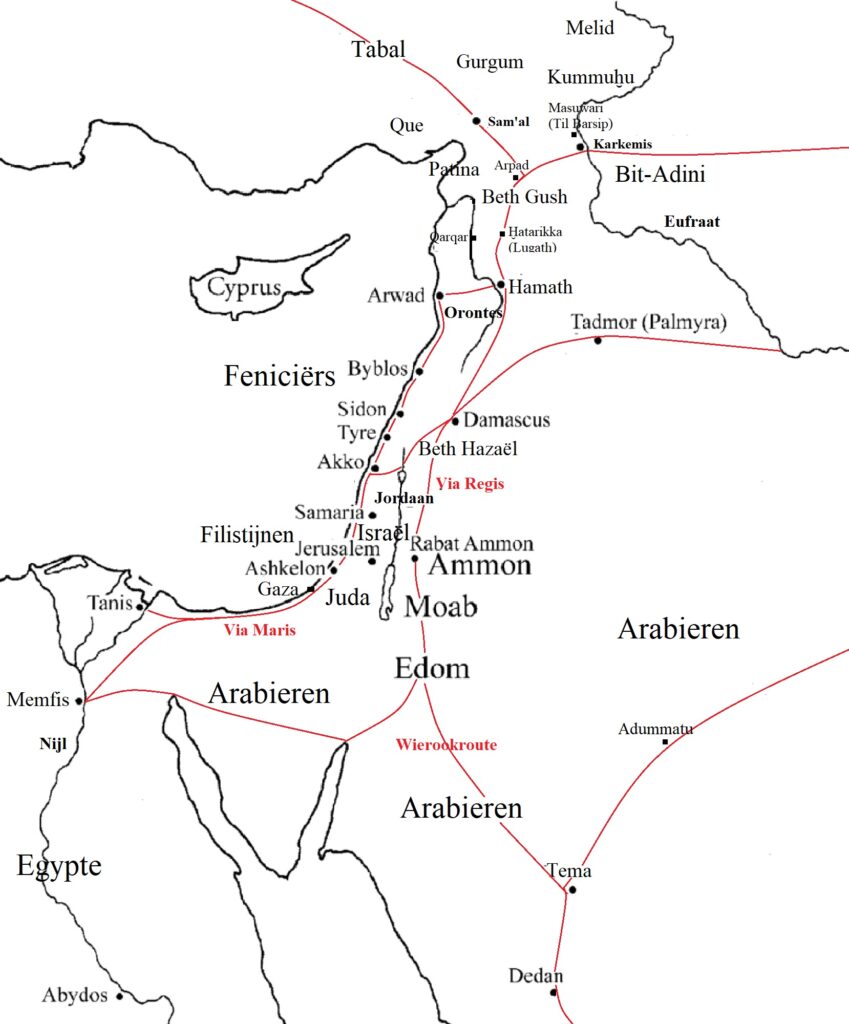

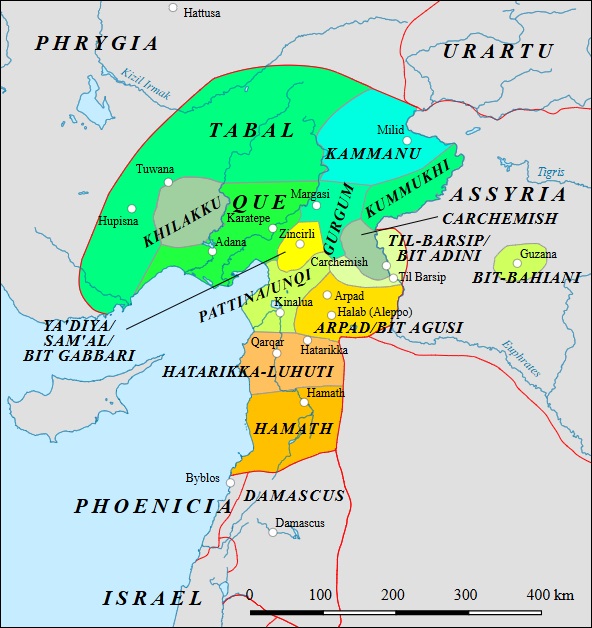

Long before Assyria annexed vast stretches of the Near East, its kings shaped the region through contracts. A network of oath-bound rulers formed the backbone of Assyria’s early imperial power. What later became one of history’s most formidable territorial empires began, surprisingly, as a diplomatic one, held together by agreements rather than governors.

In the ninth century BCE, Assyrian expansion moved outward from the Tigris Valley not through the wholesale takeover of foreign lands, but through a web of treaties. When an Assyrian king campaigned beyond his borders, he often chose not to dismantle local governments, but to bind their rulers through a sacred agreement. The local king would remain on his throne, keep his palace officials, and preserve internal autonomy. The state continued to function under its own laws and traditions.

What changed was its foreign policy. The ruler now recognized the Assyrian king as his superior and aligned himself with Assyria’s interests. The result was a form of imperial influence built not on direct rule but on managed sovereignty: kings ruled their own kingdoms, but in matters of diplomacy and war they were tethered to Assyria. The effect was a hegemonic order that allowed Assyria to expand its influence quickly and with remarkable efficiency.

Continue reading “Assyria, an empire of oaths”