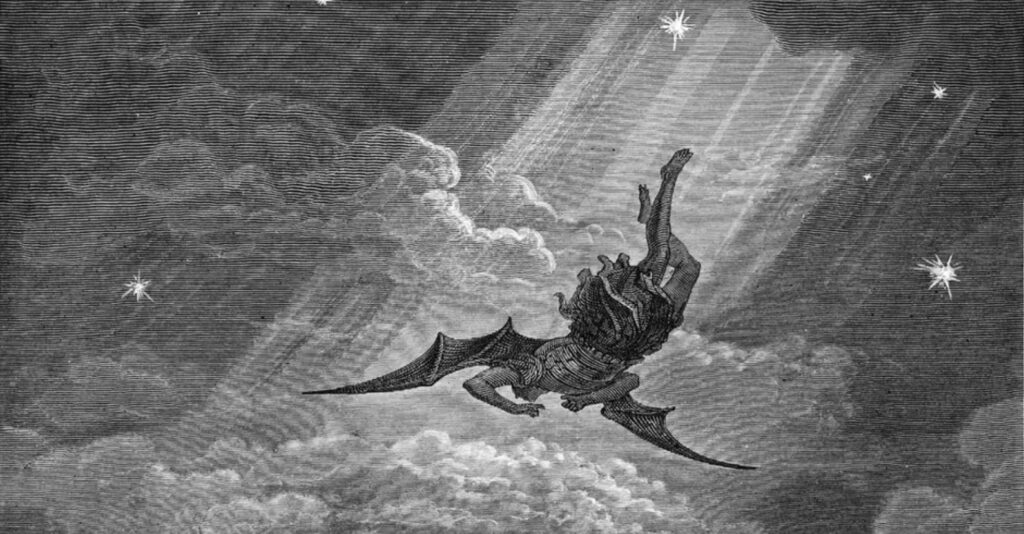

We all know the story. Or at least, we think we do. Once, the brightest of all the angels, Lucifer, grew proud. Unwilling to serve, he led a revolt in heaven, was cast down by God, and became Satan, ruler of hell. The proud light-bearer became the prince of darkness.

This story has echoed through the centuries as the archetype of hubris and humilitation. Its most famous telling is found in John Milton’s Paradise Lost (1667), where Lucifer — or Satan — is portrayed as a tragic, defiant hero, declaring:

“Better to reign in Hell, than serve in Heaven.”

Milton’s poetry fixed the myth in the Western imagination: the angelic rebel who fell from heaven through pride. Yet for all its influence, the story of Lucifer’s fall is not found anywhere in the Bible. It is the product of centuries of reinterpretation: an intricate fusion of Near Eastern mythology, Hebrew poetry, and early Christian theology.

The seed of the myth lies in one short but vivid passage: Isaiah 14:12–15. To understand how that passage evolved into the Christian legend, we need to return to its original meaning: a political taunt aimed not at a fallen angel, but at a mortal king.

“How you have fallen from heaven”

In the fourteenth chapter of Isaiah, the prophet addresses the downfall of a tyrant. He begins with a funeral dirge, mocking the pride of the once-mighty king of Babylon:

“How you have fallen from heaven,

morning star, son of the dawn!

You have been cast down to the earth,

you who once laid low the nations!You said in your heart,

‘I will ascend to the heavens;

I will raise my throne

above the stars of God;

I will sit enthroned on the mount of assembly,

on the utmost heights of Mount Zaphon.

I will ascend above the tops of the clouds;

I will make myself like the Most High.’But you are brought down to the realm of the dead,

to the depths of the pit.”

— Isaiah 14:12–15 (NIV)

In Hebrew, the fallen figure is called Helel ben Shachar, literally “Shining One, son of the Dawn.” The Greek translators of the Septuagint rendered this as Heōsphoros, “bringer of the dawn,” and Jerome’s Latin Vulgate turned it into Lucifer, “light-bearer.” In its original setting, however, the passage had nothing to do with Satan or fallen angels. It was a satire directed at a Babylonian monarch, mocking his arrogance in the face of divine judgment.

The prophet’s imagery is biting. The proud king imagines himself ascending the heavens, enthroned “above the stars of God.” He claims a divine status reserved only for the Lord. But his fate is the opposite: humiliation, death, and descent into Sheol, the shadowy underworld. The kings of the nations rise from their thrones to greet him with sarcasm:

“You also have become weak, as we are;

you have become like us.”

— Isaiah 14:10 (NIV)

And later, the oracle closes with a particularly cruel line:

“You will not join them in burial,

for you have destroyed your land

and killed your people.

Let the offspring of the wicked

never be mentioned again.”

— Isaiah 14:20 (NIV)

In other words, this is not the story of an angel’s fall, but of a king’s ruin, his body left unburied in a foreign land.

Which king of Babylon?

For centuries, commentators have assumed that this “king of Babylon” refers to Nebuchadnezzar II, destroyer of Jerusalem in 586 BCE. But the details do not fit. Nebuchadnezzar died peacefully in his palace after a reign of forty-three years. Far from dying “away from home,” he was buried with honor in Babylon.

A more plausible candidate is Sargon II of Assyria (r. 722–705 BCE), a contemporary of Isaiah. Although he called himself “king of Assyria”, Sargon also seized the throne of Babylon, styling himself its ruler after overthrowing the popular king Merodach-Baladan. To many in the Near East, this would have been nothing short of sacrilege: Babylon was a sacred city, its kingship bestowed by the gods. For an Assyrian usurper to wear that crown was to disturb the divine order itself.

Sargon was indeed a conqueror “who laid low the nations.” He invaded Israel, captured Samaria, deported its people, and annexed much of the Levant. His empire tore up boundaries and transplanted populations. Policies that, from the Judean perspective, were a kind of cosmic rebellion, a mortal reaching too high. Indeed, Isaiah had criticised this king for this reason before.

Like the taunted king of Isaiah 14, Sargon died far from home. According to Assyrian records, he was killed in battle in the mountains of Anatolia. His body was never recovered. To the ancient mind, such a fate was ominous: to die unburied in foreign soil was to be denied entry into the world of the dead.

This detail resonates strongly with Isaiah’s prophecy:

“Those who see you stare at you,

they ponder your fate:

‘Is this the man who shook the earth

and made kingdoms tremble…?’

…You are cast out of your tomb

like a rejected branch;

you are covered with the slain,

with those pierced by the sword.”

— Isaiah 14:16, 19 (NIV)

The passage fits Sargon almost perfectly: a king who exalted himself to heaven, who reigned briefly as “king of Babylon”, who died in a strange land, and whose body was never buried.

An older myth beneath the surface

Yet Isaiah’s poem draws on imagery that is far older than Sargon. Imagery that reaches back to the mythic imagination of Canaan.

The name Helel ben Shachar itself belongs to that older world. Helel (“shining one”) derives from the Semitic root hll, “to shine,” while Shachar (“dawn”) is known from Ugaritic texts as a minor god, twin brother of Shalim (“dusk”). The two were sons of the high god El, and together they represented the morning and evening stars. That is, the planet Venus in its two appearances.

Many scholars now believe that Helel ben Shachar was not just a poetic metaphor, but a Hebrew echo of the Canaanite god Athtar, the astral deity identified with Venus. In the Ugaritic myths from Late Bronze Age Syria, Athtar is portrayed as an ambitious but ultimately subordinate god. When the supreme god Baal dies and his throne on Mount Zaphon stands empty, Athtar ascends the divine mountain to claim kingship. The text tells us:

“Then Athtar the Terrible went up the Mount of Baal;

he sat on the throne of Aliyan Baal.

But his feet did not reach the footstool,

his head did not reach the top of its back.

So Athtar the Terrible said:

‘I cannot be king on the throne of Baal.’

Athtar the Terrible came down; he ruled over the earth.”— KTU 1.6 I 44–54 (Gibson, Canaanite Myths and Legends, 2nd ed., 1978)

The parallels with Isaiah 14 are striking. Both Helel and Athtar are personifications of the morning star: bright, ascending, but doomed to fall. Both seek to mount the “mount of assembly on the utmost heights of Zaphon” (Isa. 14:13), the cosmic mountain of the gods. And both are cast down to the lower realm, unable to sustain the throne they tried to seize.

In other words, Isaiah’s Helel ben Shachar was likely modeled on Athtar, the West-Semitic Venus god whose myth of failed ascent was well known in the Levant. The prophet’s audience would have recognized the allusion immediately. Isaiah took this familiar mythic image — the proud star who tries to rise above his station — and repurposed it as political satire, mocking the arrogance of a mortal king who sought to rival the divine.

From morning star to fallen angel

Centuries later, when Jewish scholars in Alexandria translated the Hebrew scriptures into Greek, Helel ben Shachar became Heōsphoros, literally “dawn-bringer.” When Jerome translated the Bible into Latin in the fourth century CE, he rendered it as Lucifer, “light-bearer.” At this stage, the term still referred simply to the planet Venus, the morning star.

But as Christianity developed its own angelology, readers began to see in Isaiah 14 something more than royal satire. Two New Testament passages helped shape this new interpretation: Luke 10:18 and Revelation 12:7–9.

In Luke 10, Jesus is speaking to the seventy-two disciples who return rejoicing that even demons submit to them in his name. His reply — “I saw Satan fall like lightning from heaven” — is best understood as a vision of Satan’s defeat, not a primordial rebellion, expressing that the power of evil is being broken through his ministry on earth.

Revelation 12, by contrast, presents an apocalyptic vision of cosmic conflict: Michael and his angels drive the dragon — identified as “that ancient serpent called the devil, or Satan” — out of heaven. This is not a literal account of Satan’s origin, but a symbolic drama of divine victory over chaos.

Read together, however, these passages seemed to describe a single event: the casting down of a proud celestial being from heaven. When paired with Isaiah’s fallen “morning star”, the identification became irresistible. Early Christian theologians such as Origen (3rd century CE) and Gregory the Great (6th century CE) fused the passages together: Helel, the “light-bearer” of Isaiah, became Lucifer, the proud angel who rebelled against God and was cast down to earth. In other words: Satan.

By the Middle Ages, this synthesis was complete. Lucifer and Satan were one and the same, the leader of the rebellious angels, the first sinner, and the eternal enemy of God. The myth that had begun as a poetic taunt against a mortal king had become a cosmic drama of good and evil.

Echoes of the older myth

It is tempting to think that the Christian identification of Helel with Satan was influenced — consciously or not — by remnants of that older Canaanite story. After all, the structure of the myth is the same: a radiant being tries to ascend the divine mountain, is cast down, and becomes a symbol of pride punished.

If so, then Christianity did not invent the idea of a fallen light-bearer. It inherited it from the deep mythological soil of the Near East. Isaiah had already drawn on that imagery to make a political point. The Church Fathers, reading Isaiah through the lens of apocalyptic and moral allegory, universalized it into a cosmic one.

What was once the story of an ambitious star became a timeless parable of hubris and fall, the same pattern that governs myths from the ancient gods to Milton’s Satan.