In 853 BCE, on the plains near Qarqar, the armies of Assyria met a coalition of kings unlike anything seen before in the Near East. Shalmaneser III, king of Assyria, boasted that he faced twelve rulers united against him: Ben-Hadad of Damascus, Irhuleni of Hamath, Ahab of Israel, and a string of Phoenician, Transjordanian, and even Arabian allies. The Assyrian king, true to form, claimed a sweeping victory: rivers dammed with corpses, tens of thousands cut down. Yet Damascus and Hamath survived, Israel endured, and Shalmaneser was forced to return again and again in later years to campaign in the west.

The contradiction is striking: if Assyria truly triumphed at Qarqar, why did the Levant remain independent for decades afterward? The answer lies not only in the battle itself, but in the long-drawn conflict over the Levantine trade system. The battle of Qarqar was no accident, nor a desperate last stand. It was a clash between two ambitious projects: Assyria’s bid to extend its authority over the western trade routes and the Levantine states’ determination to keep that system in their own hands.

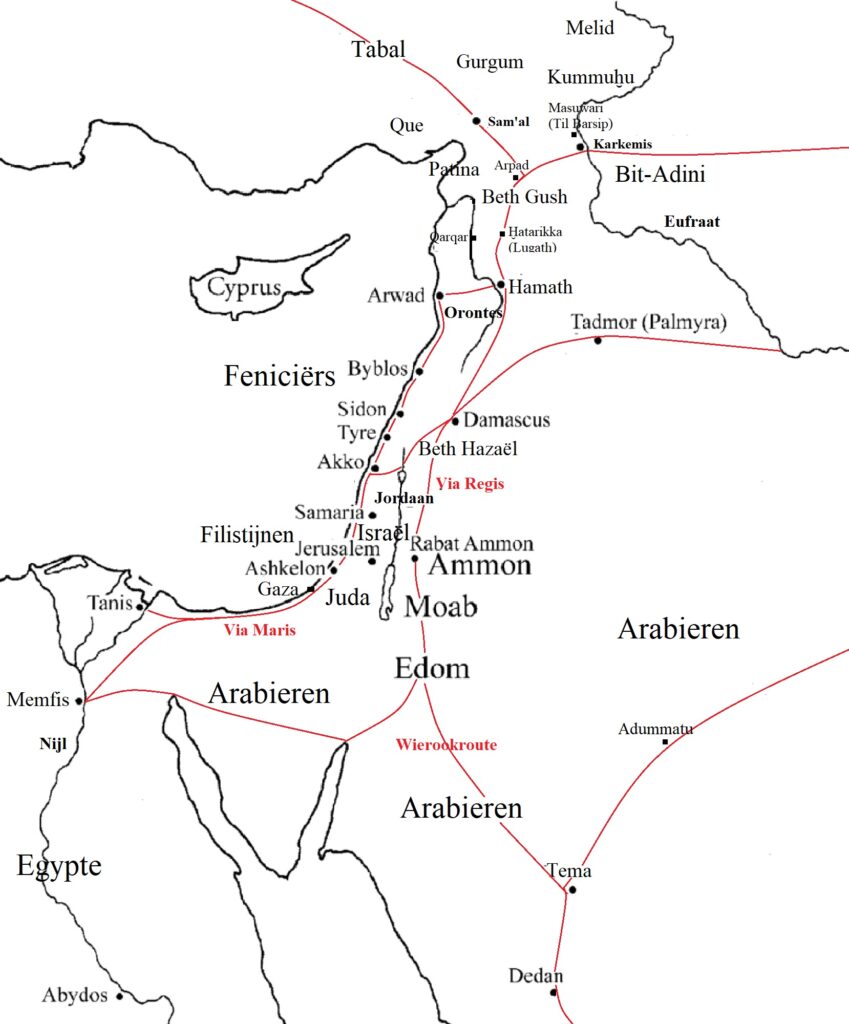

The Levant: crossroads of the ancient world

The Levant was more than a patchwork of small kingdoms. It was the connective corridor of the Near East, a narrow strip of land where sea, mountains, and desert compressed trade routes into concentrated arteries. Whoever controlled those corridors controlled the flow of wealth between the great centers of Egypt, Mesopotamia, and Anatolia.

Caravans from Arabia brought incense, myrrh, and spices northward, funneling through Damascus toward the coast. Along the Orontes River lay fertile valleys and fortified cities, including Hamath, which linked inland Syria to Anatolia and Mesopotamia. Israel straddled the Jezreel and Megiddo passes, chokepoints for overland traffic between Damascus and the Phoenician coast. The Phoenician ports themselves — Byblos, Arwad, Sidon, Tyre — served as maritime hubs, importing copper, wine, and oil, and exporting cedar, textiles, and glass. Even Egypt remained entangled in Levantine affairs, as its own prosperity depended on coastal and caravan trade. To the east, Transjordanian states like Ammon, Moab and Edom acted as intermediaries, while Arabs carried their camel caravans across the desert highways.

This network made the Levant rich, but also vulnerable. Empires on either side, Egyptian or Mesopotamian, always sought to dominate it.

Assyria on the Euphrates frontier

Assyria’s thrust into Syria did not come from a position of invincibility. For much of the 10th century BCE, Assyria had been on the defensive. Aramaean tribal states controlled the Euphrates and Ḫabur valleys and their raids reached deep into Assyrian territory.

Only under Ashurnasirpal II (883–859 BCE) did Assyria reassert control, driving the Aramaeans back and rebuilding provincial authority in its western steppe. His son, Shalmaneser III, inherited this restored base. With his homeland secure, he could now look west, toward the wealth of Syria and the Levantine trade corridors.

The fall of Bit-Adini

The key to the west was Bit-Adini, a kingdom under king Ahuni that straddled the Euphrates. Its fortresses controlled the river crossings and thus the gateway into Syria.

Ahuni forged a coalition of allies to resist Assyria: Sangara of Carchemish, Sapalulme of Patina, Hayyanu of Samʾal, and other rulers along the Euphrates and in northern Syria. For several years, this anti-Assyrian front held its ground. Coalition diplomacy, we see, was already a feature of Syrian politics well before Qarqar.

Shalmaneser crossed the Euphrates repeatedly, besieged Ahuni’s strongholds, and finally broke the alliance. Ahuni fled west but was captured. Remarkably, Shalmaneser spared his life and resettled him in Guzana (modern Tell Halaf). Mercy, in this case, served strategy: Assyria was presenting itself not only as conqueror but as legitimate overlord.

With Bit-Adini absorbed, Assyria gained its first permanent foothold west of the Euphrates. Carchemish and Kummuḫu soon sent tribute. The road into Syria lay open, and the rulers of Damascus and Hamath could see where events were heading.

The road to Qarqar

Shalmaneser pressed on. He crossed the Euphrates again, received tribute from Carchemish and Kummuḫu, and moved south through Aleppo. In Hamathite territory, he captured several royal cities — Atinnu, Pargâ, and Arganâ — burning their palaces and claiming to have subdued Hamath. But this control was fleeting. Irhuleni of Hamath remained in power and soon after became one of the architects of the great coalition.

The coalition of Qarqar was no hasty improvisation. It was a formidable diplomatic achievement. Bringing together twelve rulers, many of them rivals, must have taken years of negotiation. Damascus and Hamath, directly in Assyria’s path, were the central players, but they managed to draw in Israel, Phoenicia, and even the Arabs and Egyptians.

This was not merely a defensive alliance. The sheer scale of the force suggests broader ambitions: to push Assyria back, to keep the Euphrates corridor from falling under its grip, and to preserve the Levantine trade network under Levantine control.

The battle

The Assyrian inscriptions list the coalition in detail:

- Damascus, under Ben-Hadad: 1,200 chariots, 1,200 cavalry, 20,000 troops.

- Hamath, under Irhuleni: 700 chariots, 700 cavalry, 10,000 troops.

- Israel, under Ahab: 2,000 chariots, 10,000 troops.

- Smaller contingents from Byblos, Arqâ, Arwad, Siʾannu, and Usnû.

- Egypt, with 1,000 men.

- Gindibu the Arab, with 1,000 camels.

- Ammon, under Baʾsa.

Shalmaneser, naturally, claimed victory. One inscription reports 14,000 enemy dead; another, 25,000. He describes rivers choked with bodies, plains too small for the fallen, cavalry and chariots captured.

But the reality is told by what followed: Damascus was not conquered. Hamath was not conquered. Israel remained independent. The Phoenician cities were not forced to submit. Shalmaneser had to campaign west repeatedly in later years, with no final breakthrough. The coalition had achieved its primary goal: halting Assyria’s advance.

Hazael’s ascendancy

Within a decade of Qarqar, Ben-Hadad of Damascus was assassinated and replaced by Hazael, a usurper who proved one of the most capable kings Damascus ever produced. Far from being crushed, Damascus entered a new phase of expansion. Hazael defeated Israel repeatedly, occupied parts of Transjordan, and pressed the Phoenician coast. For a generation, Damascus was the hegemon of the southern Levant.

Assyria, meanwhile, turned its attention elsewhere. Only in the early 8th century, under Adad-nirari III, did it return in force. Hazael was compelled to send tribute once, but that act did not mark permanent subjugation. Damascus quickly resumed its independence and only decades later would Assyria finally dismantle its power.

Thus, the aftermath of Qarqar is telling: far from heralding Assyrian domination, it was followed by a Damascene resurgence that reshaped the balance of power.

Interpreting Qarqar

How should we interpret Qarqar? The traditional view casts Assyria as aggressor and the Levant as defender: Shalmaneser pushed west, the Levant reacted. There is truth in this, but it overlooks the agency of the Levantine states.

The coalition was not a panicked improvisation. It was a carefully constructed diplomatic project, likely years in the making, rooted in the shared interest of preserving control of the Levant’s trade arteries. It was not merely defensive but carried its own ambitions: to confine Assyria to the Euphrates and ensure that Levantine kings — not Assyrian officials — dictated the flow of goods and tribute.

This was a classic balance-of-power moment: local states aligning to resist a rising hegemon. From a constructivist view, it was a clash of political orders — Assyria’s universal kingship, demanding submission and tribute, versus a Levantine system of overlapping but independent powers managing their own trade.

The truth lies in between. Assyria was advancing, but the Levant was not simply reacting. Both sides sought to dominate the same network, and Qarqar was their collision point.

Conclusion

The Battle of Qarqar deserves to be remembered not only as an Assyrian campaign but as a story of Levantine agency. Damascus, Hamath, Israel, and their allies did not merely endure Assyrian aggression: they built alliances, mobilized resources, and fought for control of the trade system that sustained them.

Shalmaneser could inscribe his victories in stone, but reality was less certain. Assyria did not conquer the Levant in 853 BCE. Instead, it faced a coalition capable of fighting it to a standstill, and in the years that followed, Damascus rose to dominate the region under Hazael.

The legacy of Qarqar is not Assyrian triumph, but Levantine resilience: a testament to the foresight, unity, and determination with which small states, in the shadow of empire, could still shape history on their own terms.