Imagine opening your inbox to find a message from the Assyrian king Sargon II (r. 722–705 BCE) himself. It begins reassuringly — “I am well, Assyria is well: you can be glad” — but quickly turns into a barrage of instructions: how to reply to Phrygia’s king, how to handle a rival vassal’s land-grab, how to manage a succession dispute, even how to stage the symbolic humiliation of local rulers. It was just another day at the office. For Aššur-šarru-uṣur, the Assyrian governor of Que — a former kingdom on the Cilician plain, now reduced to provincial status — diplomacy, intelligence, and administration were part of the same job description.

A letter like this is not only a fascinating glimpse into daily imperial business; it is also a crash course in how the Assyrian Empire managed its fragile seams. To appreciate it fully, we need to look at the wider historical and geopolitical context.

A sign of goodwill

The name that leaps from the letter is Midas of Phrygia, a formidable monarch who ruled from Gordion, a city strategically placed on the Anatolian plateau. In the late 8th century BCE, Midas consolidated power over the central plateau, commanded rich agricultural lands, controlled trade routes between east and west, and built fortifications on a scale that impressed even his enemies. Archaeology at Gordion has revealed massive city walls and rich burials from his reign, underscoring Phrygia’s wealth and influence.

For Assyria, Phrygia was a formidable new presence on the empire’s western flank. Wealthy and militarily strong, it posed a danger in its own right. Its politics, however, lay outside the Mesopotamian tradition: loyalties were fluid, diplomacy unpredictable. Worse still, Phrygia often cooperated with Urartu, Assyria’s chief rival in eastern Anatolia. Together, Urartu and Phrygia could squeeze Assyria’s frontier provinces in a pincer.

That is what makes this letter so striking. Sargon reports with undisguised joy:

“This is extremely good! My gods Aššur, Šamaš, Bēl and Nabû have now taken action, and without a battle … the Phrygian has given us his word and become our ally!”

What exactly had happened? Aššur-šarru-uṣur informed the king that Midas had sent him 14 men from Que. These men had originally been dispatched years earlier by Urik of Que, the last independent king of the region, who had since been deposed by Shalmaneser V (r. 727-722 BCE) and replaced by an Assyrian governor. In sending envoys to Urartu, Urik had sought to play Assyria’s enemies against one another, a dangerous move that later came back to haunt him.

Midas, meanwhile, saw an opportunity. By “delivering” these men to the Assyrian governor, he simultaneously exposed Urik’s old act of treachery and demonstrated his own usefulness as an ally. What could have been remembered as a quiet piece of double-dealing by a dethroned local king was transformed into a diplomatic coup for Sargon.

This is why the king was so glad. Without raising a sword, the empire had gained a powerful new partner, weakened Urartu’s network, and strengthened Assyrian leverage over Que. For a king constantly balancing wars on multiple fronts, such a turn of events was indeed “extremely good.”

Returning the favor

But Sargon knew such goodwill needed careful tending. He instructed his governor:

“Do not cut off your messenger from the Phrygian’s presence. Write to him in friendly terms and constantly listen to news about him, until I have more time.”

In other words: keep the correspondence alive, keep the relationship warm, and keep the intelligence flowing. Midas’ approach was too valuable to let lapse.

The king also told his governor exactly how to handle the delicate issue of Phrygian fugitives who had sought asylum in Assyria. They were not to be sheltered or used as bargaining chips, but promptly returned with a flattering message:

“Do not hold back even a single one of the Phrygians at your court, but send them to Midas immediately! Write to him like this: ‘I wrote to the king my lord about the men of Que whom you sent to me, and he was extremely pleased … Thus at the king my lord’s behest I am sending you these men.’”

This was more than diplomacy, it was theatre. By returning fugitives, Assyria showed respect for Midas’ authority, while the carefully scripted letter framed the act as a gesture of imperial goodwill. For Sargon, this was how empires built alliances: through words as much as through armies.

A fractured landscape

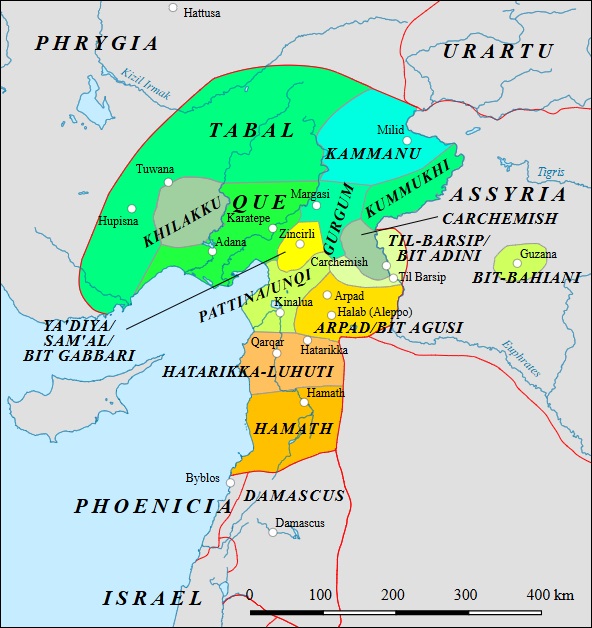

The letter also shows how the Anatolian frontier of the empire was a diplomatic minefield. Ancient Hittite lands had splintered into a patchwork of Neo-Hittite and Aramaean principalities: Tabal, Que, Gurgum, Melid, Carchemish, Sam’al. Each was ruled by a local dynast who styled himself “king,” nominally a vassal of Assyria but in practice fiercely independent. None was strong enough to dominate the rest, yet none stopped trying.

This fragmentation bred constant manoeuvring. Rulers like Urpala’a and Kilar, or tribes like the Atunnaeans and the Istuandaeans seized towns, tested borders, or courted foreign allies. It fell to the governor to keep this volatile landscape in check and Sargon’s detailed instructions reveal just how delicate the balance of power really was.

Urpala’a: wavering loyalty

The governor reported that “a messenger of Urpala’a came to me for an audience with the Phrygian messenger.” Sargon replies with biting sarcasm: “Let Aššur, Šamaš, Bēl and Nabû command that all these kings should wipe your sandals with their beards!”

The scene shows Urpala’a, king of the city of Tuwana (known in Greek as Tyana), maneuvering to insert himself into the new Phrygian-Assyrian relationship. His behavior raised suspicions. Would he slip away from Assyria if Phrygia proved more attractive? The king’s exaggerated blessing turns the incident into theatre: rather than let Urpala’a appear as an equal partner, Sargon insists he must show abject submission.

Kilar: the danger of equals

Another local ruler, Kilar, requested an alarming concession: “Kilar has requested from me four districts, saying: ‘Let them give them to me.’”

Sargon’s reply is sharp: “Should you give these four districts to Kilar, would he not become your equal, and what would you yourself be ruling over as governor then?” For Assyria, this was a red line. Governors were to maintain their own superiority over local rulers, and by extension, the king’s supremacy. Granting Kilar more land would upset that hierarchy, so Sargon instructs his governor to reassure Kilar instead: “Eat your bread and drink your water under the protection of the king, my lord, and be happy.” In other words, be content and stop grasping for more.

The Atunnaeans and the Istuandaeans: opportunistic raiding

The letter also reports unrest on the margins: “Urpala’a may slip away … on account of the fact that the Atunnaeans and Istuandaeans came and took the cities of Bit-Paruta away from him.”

Here we glimpse the inhabitants of Atunna and Istuanda, two cities in the region of Tabal, exploiting instability to seize towns. Their raids threatened to destabilize Assyria’s vassal network, prompting fears that Urpala’a might defect. Yet Sargon reassures his governor: with Phrygia now on Assyria’s side, such local uprisings could be crushed from both directions — “You will press them from this side and the Phrygian from that side so that … you will snap your belt on them.”

Managing people as diplomatic currency

Another striking element of the letter is how people themselves are treated as instruments of diplomacy. When the local ruler Balasu was removed from power, Sargon instructs his governor:

“The day you see this letter, appoint his son in his place over his men. … As for him, let one of your ‘third men’ pick him up post-haste and let him come here. I will speak kindly with him and encourage him … and in due course I will send word and have his people returned.”

Balasu is a minor figure in the historical record, a local dynast somewhere on the Anatolian frontier, but his case illustrates a larger pattern. Rather than simply eliminating a rival, Assyrian policy often sought to control succession and turn former leaders into manageable dependents. Balasu’s son could be installed immediately to maintain continuity, while Balasu himself would be escorted into “honorable exile” at the royal court. There he could be flattered, monitored, and kept out of trouble until the king decided to restore or relocate him.

This practice reflects a long-standing imperial logic. Exile was not always a punishment. It could also be a tool of integration. By removing influential leaders from their home base, Assyria reduced the risk of rebellion, but by treating them with courtesy at court, it also signalled magnanimity and offered a path back into the fold. Populations could be resettled to more secure locations or even allowed to return later, binding them more closely to the empire.

Succession, exile, and resettlement, then, were not incidental matters. They were essential tools of frontier management. For a governor, handling people in this way was as important as enforcing tribute or negotiating alliances. In Assyrian diplomacy, human lives were currency, traded, transferred, or relocated to keep the imperial system balanced.

Conclusion

Sargon’s letter shows a governor expected to be politician, commander, diplomat, and administrator all at once. But it also reflects the wider geopolitics of the late 8th century BCE: the rise of Phrygia, the fractured patchwork of Neo-Hittite states, and the constant dance between governors and vassal kings.

Imperial power in the provinces was never simple domination. It depended on governors who could navigate a volatile landscape, translate royal orders into diplomatic gestures, and keep a fragile balance of power intact. That Sargon felt the need to write such a detailed letter shows just how vital, and how precarious, this work was.