When we think of the Assyrian Empire at its height, we often imagine an unstoppable war machine. The royal inscriptions of kings like Esarhaddon certainly encourage this picture: Assyria is always victorious, its enemies always crushed or submissive, its rulers described as the unquestioned masters of the Near East. Yet if we shift our gaze away from the official record and look instead at other genres of texts, a different story emerges. One in which Assyria’s supremacy was far from guaranteed and local rulers in the empire’s periphery could pose serious challenges.

Nowhere was this more apparent than in the Zagros mountains to Assyria’s east. This rugged region in western Iran was home to dozens of small city-states and tribal groups, each ruled by a local “city-lord” (bēl āli). These rulers were technically Assyrian vassals, bound by treaty to provide troops, tribute, and loyalty. In reality, however, their allegiances were fluid. Some cooperated when it served their interests, others plotted behind the empire’s back, and rivalries among them often flared into violence. To complicate matters further, the Zagros served as a corridor for nomadic powers such as the Cimmerians and Scythians, whose raids could destabilize the region overnight. For Esarhaddon, holding the loyalty of these eastern vassals meant navigating a web of ambitions, rivalries, and external threats.

This precarious balance comes to life in the Assyrian oracle texts. Unlike royal inscriptions, these texts do not celebrate victories but record uncertainty. Their format is highly formulaic: the king poses a specific question to the gods – usually Shamash or Ishtar – about a suspected threat, the diviner conducts an extispicy ritual, inspecting the liver and entrails of a sacrificial sheep, and the physical signs are carefully noted down. What survives are the questions and omens, not the divine answers. And precisely because of that, they provide us with an unfiltered glimpse into what worried the Assyrian court: which vassals might rebel, which alliances might form, and where imperial control seemed most fragile.

Among the names that recur with striking frequency in these questions is Kaštaritu, city-lord of Karkaššî. His prominence in Esarhaddon’s oracles shows that he was regarded as far more than a minor provincial chief. Even his name is telling: Kaštaritu, an Assyrian rendering of the local Northwest-Iranian form khšatrita, literally means “little king.” The term is cognate with the later Persian šāh (“king”) and suggests the elevated, quasi-royal authority such Zagros rulers could claim. The precise location of his city, Karkaššî, remains uncertain, though it was likely near Kišassu, a fortified Assyrian trade colony in the Kermanshah region.

The oracle questions about Kaštaritu cover an astonishing range of possibilities. Taken together, they offer a catalogue of what a powerful vassal might do when confronted with Assyrian domination. They show us not so much what Kaštaritu actually did, but what the Assyrian king feared he might do—and by extension, what rulers of his rank across the empire were capable of.

Again and again, Kaštaritu appears as a would-be alliance builder. One question records him writing to another Zagros lord, Mamitiaršu, urging him to “act together and break away from Assyria.” The diviners immediately ask: “Will Mamitiaršu listen to him? Will he comply? Will he become hostile to Esarhaddon, king of Assyria, this year?” This fear of secret letters and shifting allegiances reflects the reality that Assyria’s treaties could not prevent vassals from conspiring behind the empire’s back.

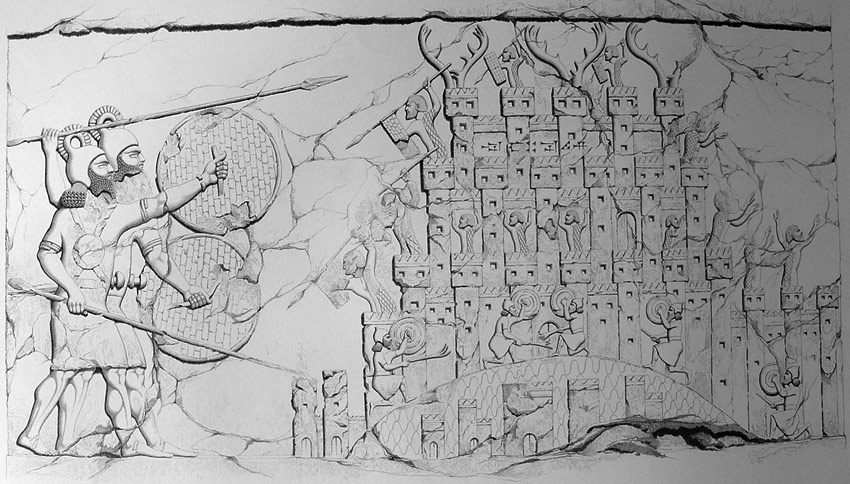

In other texts, the threat grows larger. Kaštaritu is imagined drawing on the manpower of neighboring peoples – the Cimmerians, the Medes, the Manneans – to attack Assyrian-held cities such as Kišassu or Karibtu. The questions carefully list every conceivable tactic: “Will they … by means of pressure, or by force, or by waging war, or by means of a tunnel or breach, or ladders, or ramps, or battering-rams, or famine, or a treaty invoking the names of god and goddess, or through friendliness and peaceful negotiations, or through any ruse of capturing a city, capture the city Kišassu?” It reads like a handbook of ancient siegecraft, and its inclusion here shows that the Assyrian court considered each of these methods a live possibility.

At times the questions betray unease about Assyria’s own defenses. In one case the diviners ask: “Should Esarhaddon add troops to the city Karibtu so that they can keep watch against the enemy … will Kaštaritu, with his troops or the troops of the Cimmerians or the Medes or the Manneans, nevertheless conquer that city, Karibtu, and will it be delivered to them?” Even reinforced strongholds were seen as vulnerable, their loyalty and survival never fully assured.

Kaštaritu also appears as a master of diplomacy and deception. One question describes him proposing a treaty with Assyria: “Tell the king’s envoy to come and conclude a treaty with me.” But the diviners immediately press Shamash: “Have truthful, sincere words of reconciliation really been sent?” Another text envisions Esarhaddon sending an envoy of his own: “If Esarhaddon, king of Assyria, sends his messenger to go to Kaštaritu, will Kaštaritu, on the advice of his counsellors, seize that messenger, question him, and kill him?” Even the most basic forms of diplomacy – sending and receiving envoys – were fraught with suspicion and danger.

Finally, the oracles contemplate the worst-case scenario: Kaštaritu openly attacking Assyrian officials and armies. One fragment asks bluntly: “Will Kaštaritu wage war … will they attack the magnates and governors, the army of Esarhaddon, king of Assyria? Will they kill, plunder?” Another ends with the ominous query: “Will Esarhaddon, king of Assyria, be troubled and angry?” Even the king’s state of mind was considered a valid matter for divine consultation, as if to acknowledge the psychological toll of perpetual insecurity.

What emerges from this collection is not the story of one man’s rebellion, but a vivid picture of the choices available to Assyria’s vassals. They could conspire, ally with outsiders, besiege cities, exploit Assyrian weakness, lure envoys into traps, or offer peace one day and war the next. These were the tools of agency at their disposal. Kaštaritu’s prominence in the oracles shows that Esarhaddon regarded him as especially dangerous, but the behaviors attributed to him were not unique. They were, in fact, the everyday possibilities of imperial politics on Assyria’s frontiers.

This is also what makes the oracles so valuable for historians. Where the royal inscriptions reduce local rulers to a simple binary – loyal allies or defeated rebels – the oracles preserve the full spectrum of possibilities in between. They remind us that Assyria’s power was never absolute, but always dependent on the shifting calculations of dozens of ambitious vassals like Kaštaritu.