At the start of this series, I asked a deceptively simple question: why did no balance of power emerge in the Iron Age Near East, even though so many strong states existed alongside Assyria? The Late Bronze Age had produced something resembling a diplomatic equilibrium among great powers. The Iron Age, by contrast, seems dominated by a single hegemon that faced rivals one after another, but never all at once.

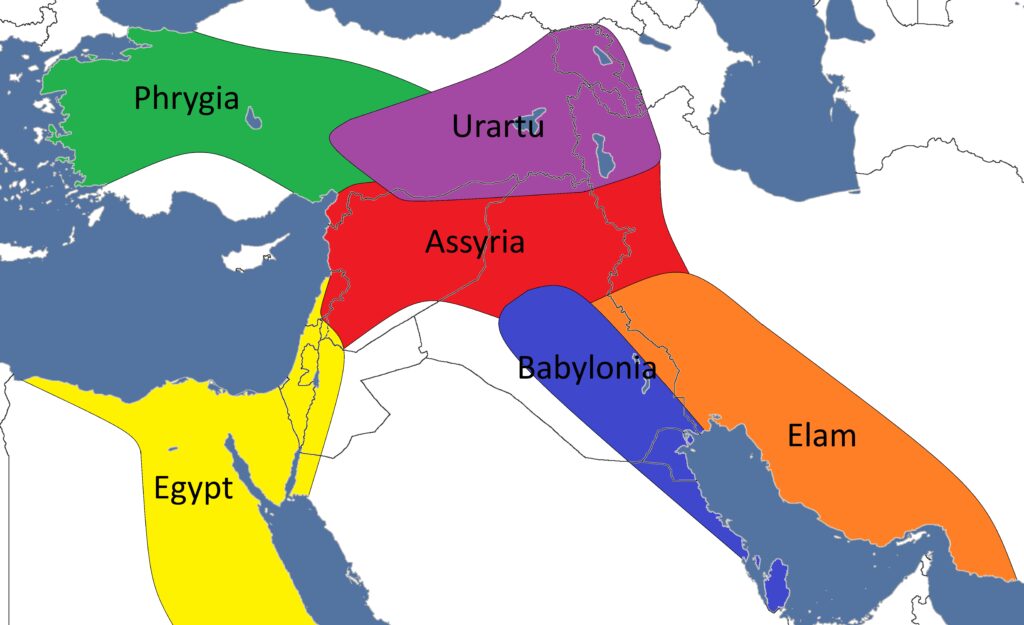

Over the past installments, we have examined those rivals individually: Urartu, Babylonia, Elam, Phrygia, and Egypt. Each possessed the potential to restrain Assyrian expansion. Each came close, in its own way. None succeeded in producing a stable multipolar order. The answer lies not in the failure of any one state, but in the historical circumstances that defined the Iron Age system itself.

Rivalry without synchronization

One of the most striking patterns to emerge from this series is the lack of simultaneity. Assyria’s rivals rarely aligned in time or purpose. Urartu challenged Assyria early, but was the first rival to be neutralized. Elam intervened repeatedly, but largely in defense of its own frontier rather than as part of a broader coalition. Phrygia matured too late and disappeared too quickly. Egypt returned only after Assyria had already established dominance in the Levant.

Balance requires more than strong actors. It requires synchronization. States must confront a hegemon together, or at least recognize a shared interest in restraint. In the Iron Age Near East, this never quite happened. Rivals emerged sequentially, not collectively. This gave Assyria a decisive structural advantage. It fought campaigns on multiple fronts, but rarely faced a unified coalition capable of reshaping the system. Instead, it dealt with crises one by one, adapting and learning as it went.

The head start of Assyria

Assyria’s greatest advantage was timing. While Egypt remained divided, while Anatolia reorganized after the Hittite collapse, and while Babylonia struggled with internal instability, Assyria developed new forms of imperial governance and military mobilization. By the time other states regained cohesion, Assyria had already transformed the rules of the game.

There is perhaps one moment when a different outcome seemed possible: the reign of Sargon II (722-705 BCE). During his rule, Assyria faced simultaneous pressures from multiple directions. Urartu intervened in the Zagros, Babylonia was in open revolt, Egypt reasserted itself in the Levant, and Phrygia emerged as a significant Anatolian power. Had Sargon failed to manage these overlapping crises, the Near East might have crystallized into a multipolar system decades earlier.

The map above illustrates one such hypothetical scenario: a Near East divided among several durable powers and Assyria confined to a more limited core. It is, of course, an alternate reality. Yet it reminds us how contingent the historical outcome truly was. Sargon’s success ensured that these rivals never coalesced into a single counterweight.

A balance that came too late

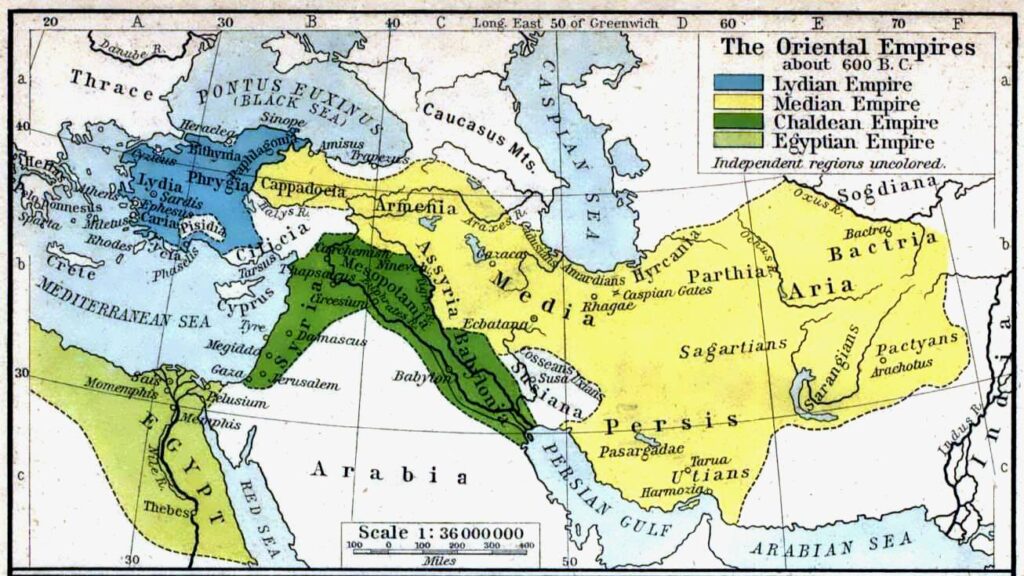

Ironically, something resembling a balance of power did emerge, but only after Assyria collapsed. In the sixth century BCE, Babylonia, Egypt, Media, and Lydia stood as major regional actors. None dominated the others completely. Diplomatic maneuvering and shifting alliances began to resemble, once again, the multipolar dynamics of the Late Bronze Age. For a brief moment, the Near East appeared to be moving toward a new “concert of powers.”

That moment did not last. A new superpower arose from the Iranian plateau. Persia conquered Media, Lydia, Babylonia, and eventually Egypt, dissolving the fragile equilibrium before it could mature into a durable system. The reasons behind Persia’s extraordinary success lie beyond the scope of this series, but they form a story worth exploring in the future.

Why balance failed

Looking back across these centuries, the failure of balance becomes clearer. It was the product of historical momentum. Assyria expanded early, encountered its rivals sequentially, and reshaped the political landscape before a coordinated response could emerge. Potential balancers either arrived too late, chose accommodation over confrontation, or disappeared before their power stabilized. Even when something resembling equilibrium finally appeared, a new force disrupted it before it could become institutionalized.

Balance, in other words, requires time, and the Iron Age Near East never quite had enough of it. Assyria did not merely defeat its rivals. It moved faster than they did, and by the time the system caught up, the world had already changed.