In the previous installments of this series, we examined rivals that clearly shaped Assyria’s rise: Urartu on Assyria’s northern frontier, Babylonia at its ideological and political core, and Elam as a persistent eastern menace. Phrygia is a more ambiguous case. It is rarely treated as a serious rival to Assyria, and even within this series its inclusion is not self-evident. I hesitated to include it.

And yet Phrygia deserves a place here precisely because of its ambiguity. It was an independent regional power that maintained diplomatic relations with Assyria without becoming a vassal. For a time, it shared a frontier with Assyria in the Taurus Mountains. Its rulers chose alliance rather than resistance. And it was the only Anatolian polity that came close to replacing the Hittite Empire. Its disappearance was not the result of Assyrian conquest, but of an external shock. Phrygia did not fail to balance Assyria. I t never had the time to become a balancer at all.

Phrygia and the Muški

In Assyrian sources, Phrygia appears under the name Muški, a people associated with central and western Anatolia. Greek authors later knew the region as Phrygia, a land that would become famous above all for one royal name: Midas.

To a classical audience, Midas is primarily a figure of myth, remembered for his golden touch and his tragic end, and often placed in the distant heroic past around the Trojan War. The historical reality is more complex. Assyrian sources refer to a ruler called Mita of the Muški who was active in the late eighth century BCE. Greek tradition, meanwhile, associates a king named Midas with the later collapse of Phrygian power under pressure from Cimmerian incursions.

Whether these references concern the same individual remains uncertain. The name “Midas” may have functioned as a dynastic or throne name rather than a personal one, and later tradition likely conflated more than one Phrygian ruler into a single legendary figure. What matters here is not the biography of a single king, but the trajectory of the Phrygian state. That trajectory makes Phrygia historically significant.

An Anatolian successor to the Hittites

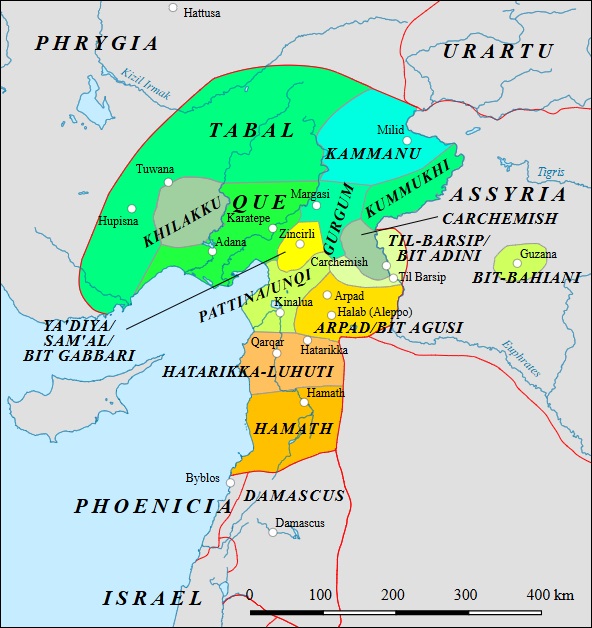

Phrygia emerged in the power vacuum left by the collapse of the Hittite Empire around 1200 BCE. For centuries, Anatolia remained politically fragmented, dominated by smaller kingdoms and local powers. By the eighth century BCE, Phrygia had consolidated enough territory, resources, and prestige to stand out as the most serious Anatolian successor to Hittite power. No other Anatolian polity of the Iron Age came as close to recreating a large-scale regional kingdom. Phrygia controlled key routes across central Anatolia, possessed a strong material culture, and commanded enough authority to be recognized by Assyria as an independent political actor. That alone sets it apart from most of Assyria’s western neighbors.

Contact without subordination

As Assyria expanded westward in the ninth and eighth centuries BCE, it inevitably came into contact with Phrygia. Unlike many polities in northern Syria and southeastern Anatolia, Phrygia never became an Assyrian vassal. There is no evidence for tribute obligations or formal incorporation into the Assyrian imperial system. Instead, relations took the form of diplomacy. Assyrian inscriptions refer to the Muški as an independent power that had to be managed rather than subdued. This was unusual in a period increasingly defined by Assyrian coercion. For a time, this independence had concrete geopolitical consequences. Assyria and Phrygia came to share a frontier in the Taurus Mountains, a sensitive zone linking Anatolia to northern Syria. Control of this region mattered for trade, security, and influence on both sides.

Alliance instead of balance

It was in this context that Phrygian rulers made a decisive strategic choice. Rather than resisting Assyria or attempting to organize an Anatolian counter-coalition, they opted for cooperation. During the late eighth century BCE, Phrygia entered into friendly relations with Assyria under Sargon II (r. 722–705 BCE). The purpose was pragmatic: securing the shared frontier and avoiding escalation in a system that increasingly rewarded speed and punished hesitation. Phrygia sought survival and stability rather than confrontation. It neither challenged Assyria directly nor attempted to replace it as hegemon. In doing so, it preserved its autonomy, but at the cost of strategic initiative.

Potential without realization

Phrygia’s case is striking precisely because it combined promise with limitation. It possessed the strongest institutional base in Anatolia since the Hittites, yet its power was largely confined to its own region. It lacked easy access to Mesopotamia or the Levant and had no network of allies capable of sustained coordination. Still, had Phrygia endured longer, it might have become a permanent western counterweight in Near Eastern politics. It occupied a position that could have mattered in a new “concert of powers.” But the Iron Age Near East was not a patient system.

The Cimmerian shock

Phrygia’s trajectory was cut short by forces entirely outside the Assyrian–Phrygian relationship. In the late eighth or early seventh century BCE, groups known as the Cimmerians swept into Anatolia from the north. Their incursions destabilized multiple regions, but Phrygia was hit particularly hard. The Phrygian heartland was overrun. Gordion was destroyed.

Greek tradition associates this catastrophe with the death of a king named Midas, though the identity of that ruler remains uncertain. What is clear is the political outcome: Phrygia ceased to exist as a major power. This matters for the larger argument. Phrygia was not defeated by Assyria. It was eliminated by an external shock before it could mature into a stable, system-shaping actor.

What Phrygia reveals about the failure of balance

Phrygia illustrates a different failure mode from the other cases in this series. It did not collapse under Assyrian pressure, like Urartu. It did not entangle and exhaust Assyria, like Babylonia. It did not oscillate between containment and cooperation, like Elam. Instead, it was removed prematurely.

Phrygia shows that the Iron Age Near East failed to produce balance not only because Assyria was strong, but because the system itself was volatile. States that might have become meaningful counterweights could be destroyed by forces beyond the Assyrian-centered political order before they ever had the chance to matter. In that sense, Phrygia was a rival that never matured.

In the next installment, we turn to the final major case: Egypt, a power that returned late to Near Eastern politics, from far away, and discovered that the world it re-entered no longer resembled the one it had once dominated.