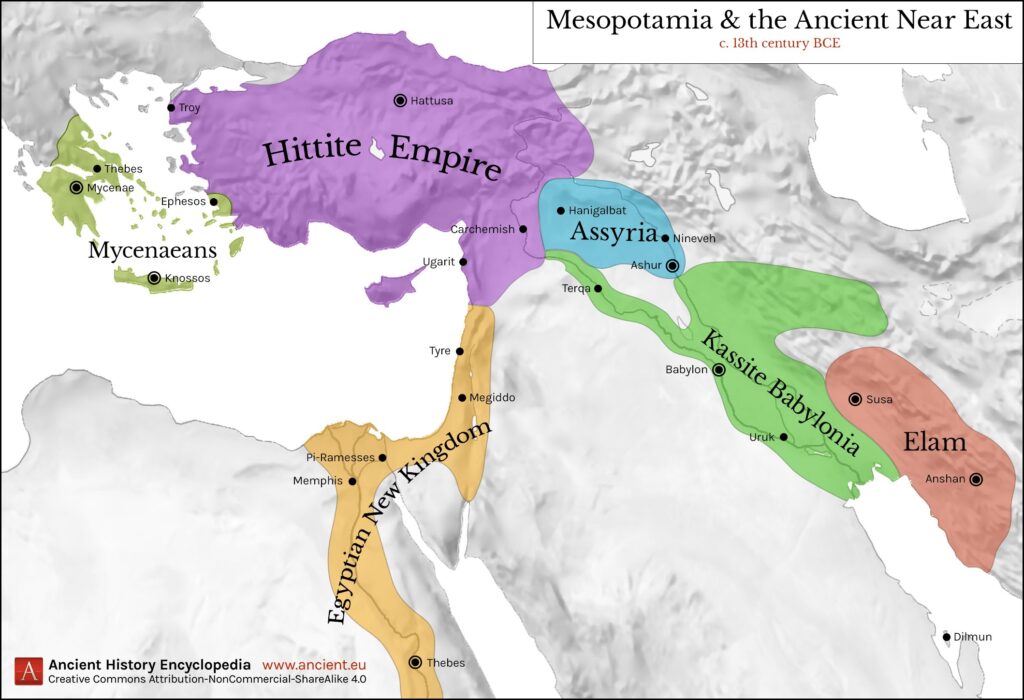

In the Late Bronze Age (1600-1200 BCE), the Near East was governed by something remarkably rare in world history: a stable balance of power. Egypt, Hatti, Babylonia, Mitanni, and Assyria recognized one another as peers. They fought wars, but cautiously. They married into each other’s dynasties, exchanged lavish gifts, and corresponded in a diplomatic language that assumed rough equality. No single power could impose its will on the others without provoking a collective response. The result was stability and a lasting peace.

This system not only limited violence, but also actively prevented the emergence of a world empire. The costs of domination were prohibitive. Any state that grew too strong risked isolation, coalition warfare, and eventual exhaustion. Power was acceptable only as long as it remained proportional.

By the eighth century BCE, however, this world was gone. In its place stood an Assyria that increasingly dominated the Near East, facing a range of rivals — Urartu, Babylonia, Elam, Phrygia, and Egypt — yet never encountering a stable counterweight comparable to the Late Bronze Age balance. The paradox is striking. Where the Late Bronze Age produced equilibrium, the Iron Age produced hegemony. Why?

To answer that question, we must begin with the collapse of the old order and with the rise of Assyria before it became the centralized imperial machine we often imagine.

The Concert of Powers

The Late Bronze Age balance of power rested on several mutually reinforcing foundations. The great states were broadly comparable in resources and military potential. Long-distance warfare was logistically difficult and expensive. Most importantly, diplomacy had become institutionalized.

The Amarna Letters offer a window into this world. Kings addressed one another as “brother”. The very language of correspondence assumed mutual recognition. Conflict was real, but bounded. Cities might be lost, dynasties might fall, but total destruction was rare. No state could escalate indefinitely without provoking a coalition response.

This balance created stability, but it was also conservative. It discouraged radical innovation in warfare, administration, and political organization. As long as the great powers remained intact, the system worked. Once they collapsed, it did not regenerate.

Collapse and the loss of restraint

Around 1200 BCE, the Late Bronze Age system disintegrated. The causes remain debated — climate stress, internal unrest, disruptions of trade, migration — but the consequences are clear. The great powers vanished or withdrew. Hatti collapsed. Mitanni disappeared. Egypt retreated from Asia. The diplomatic culture that had sustained parity eroded.

Fragmentation followed and new states emerged in a political environment without shared norms of restraint. There was no longer a “club” of peers capable of enforcing balance. The Iron Age Near East was structurally different. Power was no longer embedded in a system of equals, but contested in a landscape of unequal, rapidly adapting polities. It was in this environment that Assyria reasserted itself.

Assyria before empire

In the ninth and early eighth centuries BCE, Assyria was not yet the centralized imperial state of Tiglath-Pileser III and his successors. It had no permanent standing army in the later sense and it did not routinely annex vast territories beyond northern Mesopotamia. Its campaigns were seasonal. Its control over much of the Near East was indirect, exercised through treaties, tribute, intimidation, and occasional punitive expeditions.

Yet even in this earlier phase, Assyria was already different from its neighbors. Assyrian kings campaigned almost every year, projecting power with unusual consistency. They developed a reputation for reliability — and ruthlessness — that made their threats credible. Their military organization, while not yet fully professionalized, was increasingly effective at rapid mobilization. Just as importantly, Assyria articulated an ideology of expansion that framed resistance as illegitimate and submission as the natural order of things. This combination allowed Assyria to act with speed in a fragmented system. It did not yet seek total domination, but it was already able to prevent rivals from consolidating power against it.

Coalitions without balance

The early Iron Age did see attempts at collective resistance. City-state coalitions formed in response to Assyrian pressure, most famously in the Euphrates region and the Levant.

The coalition supporting Bit-Adini and the alliance confronted by Shalmaneser III at Qarqar in 853 BCE are often cited as evidence of balancing behavior. In reality, these coalitions reveal the limits of Iron Age counter-power. They were ad hoc, reactive, and fragile. They united states with divergent interests for a single campaign or crisis, not for sustained strategic coordination.

Crucially, these coalitions were not rivals to Assyria in and of themselves. They lacked centralized command, long-term political cohesion, and the capacity to project power beyond their immediate region. Once defeated, or simply outlasted, they dissolved. Assyria, by contrast, returned the following year.

Coalitions could slow Assyrian expansion, they could raise its costs, but they could not produce a new balance of power.

Rivals but no counterweight

By the eighth century BCE, Assyria faced a landscape crowded with plausible challengers. Urartu emerged as a powerful kingdom in the Armenian highlands, threatening Assyria’s northern flank and competing for influence over its vassals. Babylonia remained a political and cultural heavyweight to the south. Elam intervened in Mesopotamian affairs to prevent Assyrian encirclement. Phrygia consolidated power in Anatolia. Egypt, once reunified, re-entered Levantine politics.

The world was becoming increasingly multipolar. Yet multipolarity alone did not produce balance. Each of these powers confronted Assyria separately, on different fronts, with different objectives. None succeeded in coordinating resistance at a systemic level. Assyria, even before its later imperial reforms, proved consistently capable of isolating threats, exploiting divisions, and preventing the emergence of a durable counter-coalition.

The central question

This is the puzzle at the heart of this series. In the Late Bronze Age, multiple strong states produced balance and restraint. In the eighth century BCE, Assyria rose to hegemony in spite of multiple strong states. The difference cannot be explained simply by Assyria’s later imperial machinery, which did not yet fully exist. Nor can it be reduced to the weakness of its rivals, many of whom were formidable in their own right. Something deeper had changed, in the structure of the international system, in the speed of military response, and in the absence of shared mechanisms for restraint.

In the following installments, each rival will be examined in turn. Not merely as an enemy of Assyria, but as a test case. Why did Urartu fail to become a lasting counterweight? Why did Babylonia entangle rather than restrain Assyria? Why did Elam’s buffer strategy collapse? Why did Phrygia never scale up? Why did Egypt arrive too late and withdraw too soon?

Only by examining these failures individually can we understand the broader failure of balance itself and why, long before Assyria perfected empire, the world around it had already lost the ability to contain power.