Allan Gluck, CC BY 4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

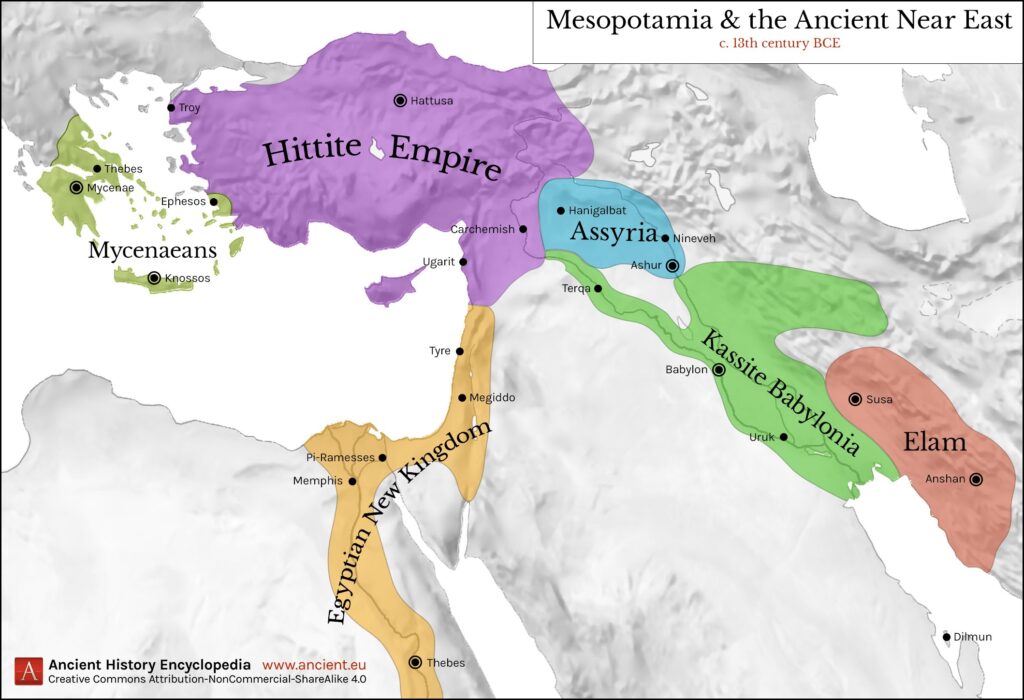

In the previous installments of this series, we saw how Urartu failed to restrain Assyria from the outside and how Babylonia — older, richer, and more prestigious — challenged it from within. In this episode, we turn eastward to a very different kind of rival. For over a century, Elam repeatedly intervened in Mesopotamian affairs, shaping the political order of the Near East. Yet unlike Assyria, it never sought to build an empire of its own.

In Mesopotamian sources, Elam often appears as a familiar villain: ruled by treacherous kings, threatening Mesopotamian kingdoms with sudden raids and inconvenient interventions. But this image obscures a deeper reality. Elam was not a marginal spoiler, but one of the oldest and most enduring great powers of the ancient Near East, with its own imperial traditions, strategic culture, and long experience in managing Mesopotamian politics. If Elam never produced balance, it was not because it lacked power. It was because it never sought hegemony — only security.

Continue reading “When balance failed (4): Elam and the politics of containment”