joepyrek, CC BY-SA 2.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Ancient Persia usually evokes images of the monumental palaces at Persepolis, the conquests of Cyrus the Great, and the legendary wars with Greece. The Achaemenid Empire is remembered as the world’s first superpower, a realm that stretched from Anatolia to India, commanding the cities along the Euphrates and the Tigris and the rich floodplains of the Nile.

It is mostly the western half of this empire that has captured the imagination of classical history. Yet beyond that well-lit world lay another half: vaster and far less known. At the eastern edge of the Iranian Plateau stretched an immense frontier where the empire bordered the steppes of Central Asia. Here lay the satrapies of Bactria, Margiana, and Sogdia: names that sound almost mythical today. To the Greeks they were remote and strange. To the Persians they were indispensable, though their voices barely echo in the surviving records.

The farther east we look, the closer we come to the origins of Iranian civilization. Long before Cyrus and Darius raised their palaces in the west, these frontier lands had already nurtured a vibrant civilization. One that may have forged the cultural and spiritual foundations of Iran itself. Archaeologists call it the Yaz culture.

A civilization without graves

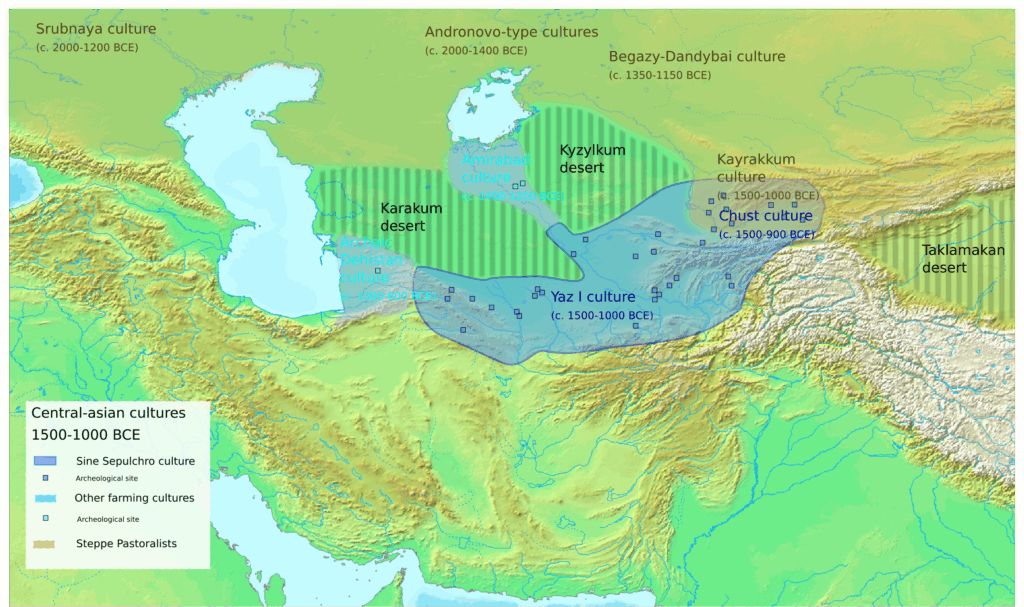

The Yaz culture flourished roughly between the 14th and 6th centuries BCE across modern Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, northern Afghanistan, and northeastern Iran. In those days, the fertile valleys of the Murghab and Amu Darya (Oxus) formed a green crescent between the deserts and mountains, a natural crossroads between East and West.

The Yaz culture emerged after the decline of the older Bactria–Margiana Archaeological Complex (BMAC), a Bronze Age civilization famous for its fortified temples, jewelry, and long-distance trade with Mesopotamia and the Indus Valley. Whether the Yaz people were newcomers or descendants of the BMAC inhabitants remains debated, but they almost certainly included communities who spoke early Iranian languages and combined the irrigation of desert oases with the herding of cattle and horses. They left behind a new kind of pottery that was simpler, plainer, and more standardized than that of their Bronze Age predecessors. The grand temples of the BMAC were largely abandoned or repurposed into smaller, fortified settlements.

In these villages, the Yaz people built their homes of mud brick and surrounded them with ramparts. They mastered irrigation and turned dry valleys into green fields. They made tools and weapons of bronze and, later, iron. But the strangest thing about them is not what they built, it’s what they didn’t leave behind: graves.

Across hundreds of Yaz sites, archaeologists have found almost no burials, an absence that continues to puzzle researchers. A few isolated Yaz-period graves have been discovered, but they are exceptional rather than typical. Where, then, were the cemeteries? Were they destroyed, hidden, or located elsewhere? One intriguing theory is that the Yaz people practiced exposure of the dead, placing corpses on towers or open ground for vultures to consume, a ritual known from much later Zoroastrian practice.

If so, it might suggest that the Yaz communities already valued the purity of natural elements — earth, fire, and water — an idea that would later become central to Iranian religion.

The voice of the Avesta

Because the Yaz culture left no writing, our only textual clues come from a different source: the Avesta, the sacred scripture of Zoroastrianism.

The Avesta is not a single book, but a diverse collection of hymns, prayers, ritual instructions, myths, and laws, composed in different periods and styles. For centuries these texts were transmitted orally by priestly lineages who memorized them with great precision, and they were written down only much later, during the late Sasanian period (3rd–7th centuries CE), more than a thousand years after their composition.

Linguistically, the Avesta was composed in Eastern Iranian dialects, closely related to the languages once spoken in Bactria and Margiana. The oldest hymns — the Gathas, attributed to the prophet Zarathustra — are generally dated somewhere between 1500 and 1000 BCE, roughly contemporary with the Yaz culture. This makes it plausible that the earliest Zoroastrian communities were rooted in the same eastern lands.

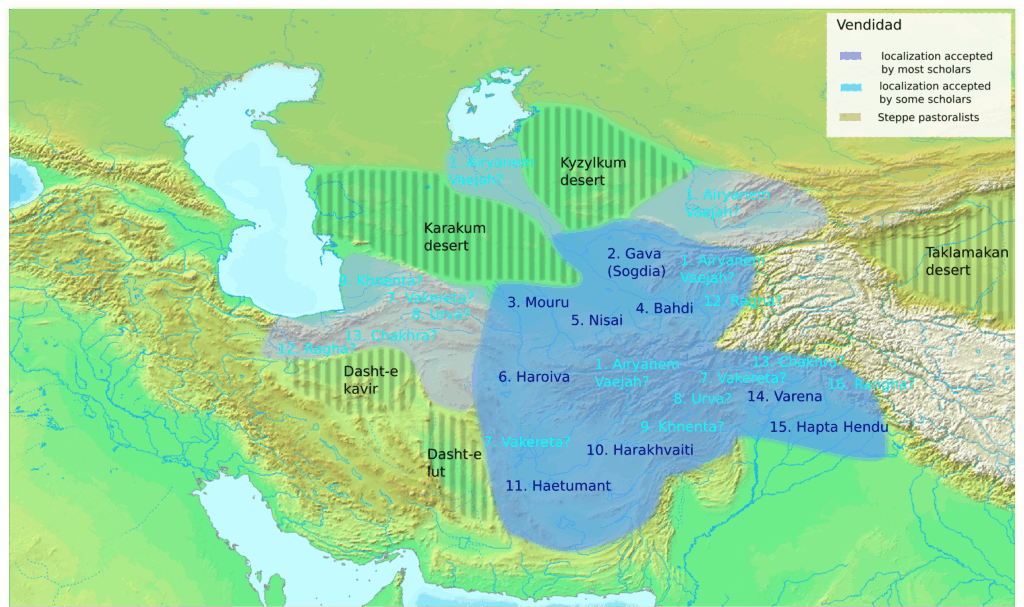

The Avesta describes a world of farmers and herders who worshipped fire, tended their cattle, and prayed for rain and fertile fields. It praises water as holy, condemns the pollution of the earth, and portrays life as a cosmic struggle between Truth (asha) and the Lie (druj). It names sixteen “good lands” created by the god Ahura Mazda: regions of rivers and mountains that many scholars identify with eastern Iran and Central Asia, including Bahdi (Bactria), Gava (Sogdia), Mouru (Margiana), Haroiva (Aria), and Harakhvaiti (Arachosia).

In other words, most scholars place the roots of Avestic religion in eastern Iran or Central Asia, in the same environment that produced the Yaz culture. Both seem to reflect a worldview shaped by irrigation, purity, and the fragile balance between life and desolation.

Of course, we cannot prove that the Yaz people were Zoroastrians. Religion evolves slowly, and archaeology rarely speaks the same language as scripture. Yet if we strip away the myths and look at the underlying culture, the parallels are intriguing.

The cradle of Iranian identity

Why does this matter? Because the Yaz culture helps explain how a shared Iranian identity began to take shape. One that eventually linked communities from the Oxus to the Zagros.

The communities of the Yaz horizon were among the earliest to speak Iranian languages, ancestors of Persian, Kurdish, Pashto, and many others. Their rituals and beliefs, preserved in the Avesta, articulated ideas that would echo across centuries: the moral order of Asha (truth), the cosmic struggle against Druj (falsehood), and reverence for Ahura Mazda, the Wise Lord. These concepts formed a spiritual vocabulary that later Iranian dynasties — from the Achaemenids to the Sasanians — would adopt and adapt, giving coherence to an empire of many tongues and traditions.

Even the very name Iran reflects this deep continuity. It derives from Airyanəm Vaējah — “the land of the Aryans” — a phrase that first appears in the Avesta as a sacred ideal rather than a political state. In this sense, the Yaz culture provided some of the cultural and religious foundations for a pan-Iranian world, one that long outlasted the empires built upon it.

Between Empire and the Silk Roads

The Yaz lands were not isolated. They sat at the meeting point of worlds, between the Iranian plateau, the steppe, India, and China. Their rivers and mountain passes became arteries of exchange long before anyone spoke of the Silk Road.

Through these corridors flowed metals, horses, lapis lazuli, and ideas. The same routes that once carried Yaz pottery and eastern dialects would later carry silk, spices, and religions. When the Achaemenids absorbed these territories, they inherited not just land, but a network, an infrastructure of connectivity that would outlive their empire and link civilizations for centuries.

By the time of Darius, Bactria and Sogdia were already known for their cavalry and their trade. Persian inscriptions mention them by name, and Greek historians later praised their wealth and skill. But beneath that Achaemenid veneer lay a much older legacy: the legacy of the Yaz.

From east to west: the journey of ideas

How, then, did the ideas of the eastern Iranians reach the west?

Most likely through migration and slow diffusion. The ancestors of the Western Iranians — early pastoral groups who had once shared a common world with the peoples of the Yaz culture in Bactria and Margiana — began to move southwest around the late second millennium BCE. They followed the foothills of the Kopet-Dagh and passed through Hyrcania and Parthia into the Iranian plateau. For centuries they lived in close contact with the sedentary Yaz communities, who cultivated the oases of Central Asia and developed many of the ideas later found in the Avesta: the worship of Ahura Mazda, the fire cult, the haoma ritual, and the moral opposition between Asha (truth, order) and Druj (lie, chaos).

From these interactions the migrating western groups absorbed much of the eastern spiritual vocabulary, though not all its theology. They adopted the great cosmic dualism and the veneration of Ahura Mazda, but without the full priestly elaboration of Zarathustra’s reform. As they settled among the older highland populations of Media and Persis, their religion fused eastern Iranian concepts with local Elamite and Zagros traditions, creating a simpler, more royal and less priestly version of the same faith.

By the time the Medes and Persians emerged in the Zagros, their religious language already bore the imprint of that shared eastern ancestry. The Achaemenid kings invoked Ahura Mazda — the same supreme god revered in the Avesta — and conceived kingship as the triumph of truth over falsehood, purity over corruption, order over chaos.

Later, under the Parthians and Sasanians, Zoroastrianism evolved into the state religion of Iran, codifying doctrines that had begun a thousand years earlier in the Yaz lands. Even as the political center of gravity moved west, the spiritual roots of Iran remained in the east, in the meeting ground where the proto-West-Iranians and the Yaz peoples once exchanged not only goods and rituals, but the moral imagination of an entire civilization.

The echo of the east

Today, the ruins of the Yaz world lie scattered across deserts and steppes, mud-brick walls crumbling under sun and wind, shards of pottery half-buried in dust. Few tourists ever visit them. Their names — Ulug Depe, Yaz Depe, Dzharkutan — mean little outside of archaeology. And yet, without these forgotten places, there might never have been a Zarathustra, an Ahura Mazda, or an Iranian civilization at all.

What makes the Yaz culture so fascinating is that it bridges worlds: between archaeology and scripture, between East and West, between the tangible and the mythic. It reminds us that the roots of great civilizations often lie far from their capitals, in the margins, the borderlands, the places that later chroniclers forgot to mention.

The Achaemenid Empire’s eastern satrapies were not just distant provinces. They were the cradle of Iranian identity, the seedbed of its religion, and the first stage of the Silk Roads. Long before the Persians marched to Greece, long before Herodotus wrote his Histories, the Iranians of the east were already building a world of their own whose echoes can still be heard in the moral language of half the world.