When we last left King Hezekiah of Judah, he was emerging as one of the most powerful rulers of the Southern Levant. Unlike many of his neighbors, he dared to test the patience of the Assyrian empire. Hezekiah strengthened his kingdom militarily, reformed its religious practices, and looked for openings in the power struggles of the wider Near East. In a world where most local rulers were cautious to the point of submission, Hezekiah stood out for his boldness.

That boldness would soon bring him into direct conflict with Sennacherib, king of Assyria.

The Assyrian backdrop

Sennacherib (r. 705–681 BCE) came to the throne under difficult circumstances. His father Sargon II (722–705 BCE) had been one of the great conquerors of his day, defeating formidable enemies like Merodach-Baladan II of Babylon and Rusa I of Urartu, while consolidating Assyrian control across the Levant and the Zagros mountains. To contemporaries, Sargon had seemed nearly invincible. Yet in 705 BCE he met a humiliating end on the battlefield, his body left behind to the enemy. To many in the region, this was no ordinary death but a sign of divine judgment: the gods themselves, it was believed, had finally turned against the Assyrian king.

The sudden death of such a powerful monarch created ripples throughout the empire. Vassals across the realm tested Assyria’s resolve, calculating that the new king might not command the same fear and loyalty as his father. Sennacherib himself seemed uneasy with the shadow Sargon’s death cast. He never mentioned his father by name in his inscriptions, and he abandoned the grand new capital of Dūr-Šarrukīn, built by Sargon to display his power, in favor of Nineveh.

In Babylonia, Sargon’s old rival Merodach-Baladan II seized his chance, returning from exile and briefly regaining the throne. In 703 BCE, Sennacherib managed to drive him out and reassert Assyrian control, but the region would remain a perennial source of trouble. Meanwhile, in the Levant, city-states and small kingdoms looked to Egypt for support, hoping that the death of Sargon might mark the beginning of Assyria’s decline.

Why Judah?

Among these restless vassals, Judah drew particular attention. Hezekiah was not only one of the most powerful rulers in the Southern Levant but also one of the most daring. His greatest provocation was the seizure of Padi, king of Ekron. Padi had remained loyal to Assyria, but Hezekiah took him hostage: an act that went far beyond the usual delays in tribute or tentative diplomacy with Egypt and Babylonia. It was a direct affront to Assyrian authority.

For Sennacherib, this was the perfect casus belli. By portraying his campaign not as an act of imperial repression but as the righteous liberation of a loyal ally, he could present himself as both just and powerful.

Securing the coast

As Sennacherib marched west in 701 BCE, the coastal states and kingdoms across the Jordan took a wait-and-see attitude. After Sargon’s death they had withheld tribute, hoping Assyria’s grip might weaken. Now, faced with Sennacherib’s army, they quickly recalculated.

“Fear of my lordly brilliance overwhelmed Lulî, the king of Sidon, and he fled afar into the midst of the sea,” Sennacherib boasts. One by one, the city-states along the coast and the kingdoms across the Jordan “brought extensive gifts… and kissed my feet.” They paid four times the usual amount to make up for the four years they had withheld tribute. Submission was a strategic move to survive, while Sennacherib’s choice to “forgive” them in exchange for payment was equally calculated: better to secure tribute than to waste resources on costly sieges.

Only Ṣidqâ of Ashkelon misjudged the situation. Sennacherib boasts: “I forcibly removed the gods of his father’s house, himself, his wife, his sons, his daughters… and took him to Assyria. I surrounded, conquered, and plundered the cities of Ṣidqâ that had not submitted to me quickly.” The brevity of this passage is telling. Unlike his detailed description of the campaign in Judah, here Sennacherib provides almost no specifics. It seems to have been an easy victory and the “surrounding, conquering, and plundering” of Ṣidqâ’s cities may have happened without much actual fighting.

The crisis at Ekron

The real flashpoint came at Ekron, where the local elites had delivered their king Padi into Hezekiah’s hands. Sennacherib records with outrage: “The governors, nobles, and people of Ekron… handed him over to Hezekiah of Judah in a hostile manner.”

To counter Assyria, Ekron allied with Egypt and Kush: “They formed a confederation with the kings of Egypt… In the plain of Eltekeh they sharpened their weapons while drawing up in battleline before me. With the support of Aššur, my lord, I fought with them and defeated them.” In the clash, “I captured alive the Egyptian charioteers and princes, together with the charioteers of the king of Kush.”

The two armies probably faced one another in a standoff, and after some show of strength the Egyptians chose to withdraw. The mention of captured nobles may hint at an exchange of hostages to save face on both sides. For Sennacherib, the episode could be framed as a victory, for the Egyptians, withdrawal avoided an unwinnable confrontation. Both sides preserved their reputations, while the fate of Ekron was left in Assyrian hands.

Ekron’s rebels paid dearly: “I killed the governors and nobles who had committed crimes and hung their corpses on towers around the city,” while those who were not guilty were spared. This rare moment of judicial selectivity hints that Sennacherib felt the need to justify his actions more than usual. Perhaps he wished to reassure allies that Assyria rewarded loyalty as much as it punished rebellion.

The campaign in Judah

Judah was next. “I surrounded and conquered forty-six of his fortified walled cities… by having ramps trodden down and battering rams brought up, the assault of foot soldiers, sapping, breaching, and siege engines,” Sennacherib writes.

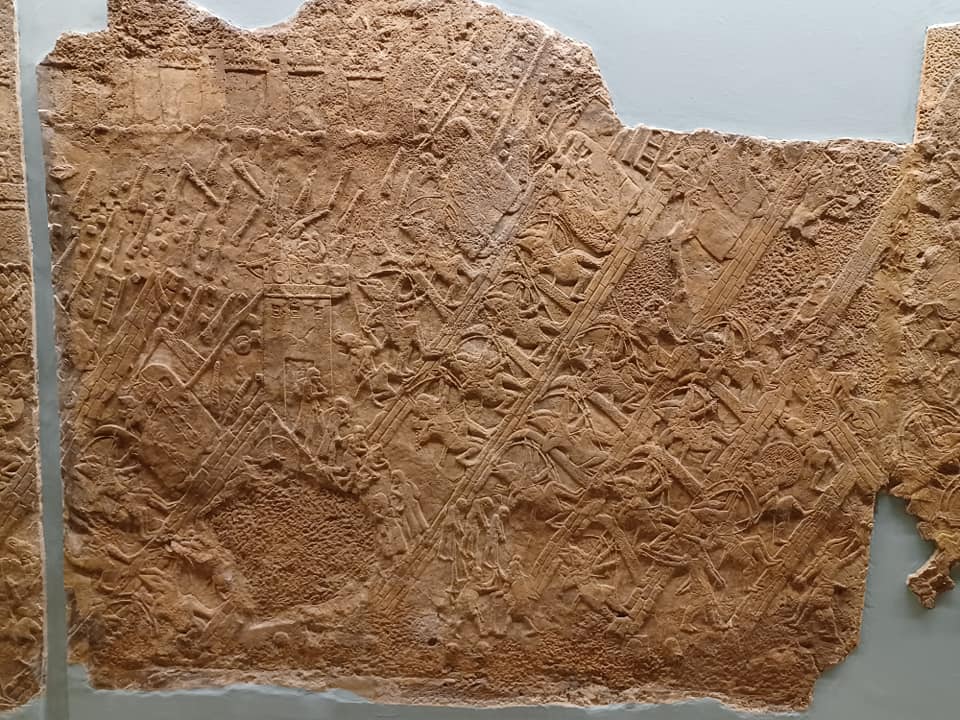

Archaeology confirms this at Lachish, a fortified city at the border of the Shephelah and the Judean hills, where Assyrian engineers constructed siege ramps and battered the walls with projectiles. The famous Lachish reliefs in Sennacherib’s palace depict the battle in vivid detail, underscoring its importance as the campaign’s centerpiece.

The devastation was enormous: “I brought out of them 200,150 people, young and old, male and female… and I counted them as booty.” This figure is surely inflated, as it is at least five times Judah’s likely population at the time, but it conveys the massive dislocation inflicted.

Jerusalem under siege

Finally, Sennacherib turned to Hezekiah himself. In his own words: “As for him, Hezekiah of Judah, I confined him inside Jerusalem, his royal city, like a bird in a cage. I set up blockades against him and made him dread exiting his city gate.” The metaphor of the “caged bird” is striking. It conveys humiliation and helplessness, but it also carefully avoids saying that the city was stormed or taken. Jerusalem, unlike Lachish, remained unconquered.

What the inscription does emphasize is submission. According to the Assyrian version of events, Hezekiah sent envoys to Sennacherib, overwhelmed by fear, and offered a lavish payment. The Bible agrees on the point of tribute. After all his fortified cities except for Jerusalem have been taken, Hezekiah says: “I have done wrong. Withdraw from me, and I will pay whatever you demand of me” (2 Kings 18:14).

The Assyrian record then revels in listing every item of wealth and prestige extracted from Judah—“30 talents of gold, 800 talents of silver… ivory beds, armchairs of ivory… his daughters, his palace women, male singers, and female singers.” The long catalog is propaganda: by enumerating tribute in painstaking detail, Sennacherib distracts from the fact that Jerusalem itself remained beyond his grasp.

At the same time, Hezekiah’s territorial gains were undone. The fortified towns he had annexed in the Shephelah were reassigned to Philistine kings: Mitinti of Ashdod, Padi of Ekron, and Ṣilli-Bēl of Gaza. His expansionist policy was reversed, his kingdom diminished, and his prestige badly damaged. Padi himself was almost certainly released at this stage, restored to his throne at Ekron as part of the Assyrian settlement.

The outcome, then, was one of humiliation without annihilation. Hezekiah kept his throne and his city, but only at the cost of tribute, territory, and pride.

The biblical account

The biblical narrative retells the same story but reframes it as a spiritual drama. After Hezekiah’s initial tribute, the text pictures Sennacherib still at Lachish, sending three senior officials – the Tartan, the Rabsaris, and the Rabshakeh – to Jerusalem. Standing at the city walls, the Rabshakeh launches into a long speech aimed not just at Hezekiah’s envoys but at the people listening from above.

He mocks Judah’s reliance on foreign aid: “Look, I know you are depending on Egypt, that splintered reed of a staff, which pierces the hand of anyone who leans on it” (2 Kings 18:21). He questions Hezekiah’s religious reforms: “If you say to me, ‘We are depending on the Lord our God’—isn’t he the one whose high places and altars Hezekiah removed?” (18:22). And most provocatively of all, he claims divine sanction: “The Lord himself told me to march against this country and destroy it” (18:25).

These lines show how well the Assyrians understood Judah’s internal politics. Hezekiah’s centralization of worship in Jerusalem had been controversial, and the Rabshakeh exploits this tension to sow doubt. His words also show how Assyrian propaganda could be adapted to local contexts: even Yahweh, he suggests, has abandoned Judah to Assyria.

But then the narrative takes a turn. “Sennacherib received a report that Tirhakah, king of Cush, was marching out to fight against him” (2 Kings 19:9). This moment is crucial. If the Egyptians advanced while negotiations were unfolding in Jerusalem, it would explain why the Assyrians never launched a full siege. The Rassam Cylinder places the Egyptian encounter earlier, at Eltekeh, and presents it as a decisive Assyrian victory. But the biblical chronology suggests otherwise: that the Egyptian threat forced Sennacherib to abort the siege of Jerusalem and move south. The discrepancy highlights how royal inscriptions could reorder events to present the most triumphant narrative.

The biblical account then layers on its theological climax. Hezekiah turns to Isaiah, who reassures him that Jerusalem will not fall. Finally, the dramatic conclusion: the Angel of Death strikes down 185,000 Assyrians in a single night, and Sennacherib retreats in defeat. This is almost certainly a later embellishment, meant to transform Judah’s survival into a miraculous deliverance. Yet even if no angel ever struck the Assyrian camp, the story captures a deeper truth: Jerusalem endured when, by all ordinary measures, it should have fallen. That survival demanded explanation, and the explanation chosen was divine intervention.

Aftermath

The results were mixed. Sennacherib devastated Judah, restored Padi, and reasserted Assyrian supremacy. Yet he did not capture Jerusalem or depose Hezekiah. The Judean king, though weakened, preserved his throne and dynasty.

Each side spun the outcome. Assyria emphasized conquest, deportations, and tribute, while Judah remembered survival and recast it as divine deliverance. In reality, compromise carried the day: Hezekiah paid off Sennacherib, Padi was restored, and the threat of Egyptian intervention discouraged a prolonged siege.

It was not total victory for either side. But in the centuries that followed, it was Jerusalem’s survival, not Lachish’s destruction, that shaped history.

Reflection

The Assyrian and biblical versions of Sennacherib’s campaign mirror one another as propaganda. The Rassam Cylinder emphasizes cities taken, enemies crushed, and tribute heaped at the king’s feet: the Bible emphasizes Jerusalem’s survival and Yahweh’s deliverance of his people. Both accounts minimize setbacks and magnify triumphs, each transforming a messy outcome into a tale of victory.

In reality, the campaign was shaped as much by negotiation and concession as by open conflict. Hezekiah lost territory, treasure, and prestige, yet he kept his city and throne. Sennacherib devastated Judah and restored order at Ekron, yet he stopped short of conquering Jerusalem outright. Each side gave ground to avoid the risks of a prolonged struggle.

This episode reminds us that Assyrian power rested not only on brutal repression but also on its ability to persuade. Minor kings were kept in line through a mixture of intimidation, incentives, calculated mercy, and, when needed, spectacular shows of force. Military conquest was one tool among many, and often not the most decisive one. What determined the outcome was not total annihilation, but the ability of both sides to frame compromise as victory.