What comes to mind when you hear the word Paradise? Perhaps you picture a lush garden filled with trees, flowers, and animals. This image is far older than our modern imaginations and has deep roots in the ancient world. In Mesopotamia, the ‘land between the rivers’, the ability to make the desert bloom through irrigation and hydraulics was seen as the very height of civilization. Kings even styled themselves as gardeners. Not hobbyists tending a backyard patch, but rulers who created vast, cultivated gardens within their cities as living symbols of their duty to uphold and restore the divine order.

Mesopotamian kings as gardeners

Take this royal inscription from the Assyrian king Sargon II (r. 722-705 BCE):

(…) the wise king who occupies himself with good matters, (who) turned his attention to (re)settling abandoned pasture lands, opening up unused land, (and) planting orchards; (who) conceived the idea of raising crops on high mountain(-slopes) where no vegetation had ever sprouted; (who) was minded to provide with rows of furrows the waste land which had known no plow under previous kings, to have (the plowmen) sing the alālu-work song, to open up for watering place(s) the springs of a meadowland without wells, and to irrigate all around (lit.: “above and below”) with water as abundant as the surge at the (annual) inundation; (…)

RINAP II – 43:34-37

Sargon II’s son Sennacherib (r. 705-681 BCE) describes one of his projects in more detail: the construction of the palace gardens in his new capital Nineveh:

Beside the city, in a botanical garden (one) pānu (in size and) a garden (one) pānu (in size) for a game preserve, I gathered every type of aromatic tree of the land Ḫatti, fruit trees of [all lands], (and) trees that are the mainstay of the mountains and Chaldea. Upstream of the city, on newly tilled so[il], I planted vines, every type of fruit tree, and olive tre[es].

For the expansion of orchards, I subdivided the meadowland upstream of the city into plots of two pānu each for the citizens of Nineveh and I handed (them) over to them. To make (those) planted areas luxuriant, I cut with iron picks a canal straight through mountain and valley, from the border of the city Kisiri to the plain of Nineveh. I caused an inexhaustible supply of water to flow there for a distance of one and a half leagues from the Ḫusur River (and) made (it) gush through feeder canals into those gardens.

RINAP III – 8:3-23

From every corner of the empire, plants, trees, and animals were gathered and displayed in a setting that combined natural beauty with cutting-edge technology. These gardens were sustained by remarkable feats of hydraulic engineering. Vast aqueducts carried water across the landscape and some scholars even suggest that an early form of the Archimedean screw was used here centuries before Archimedes himself was born.

The myth of the Hanging Gardens

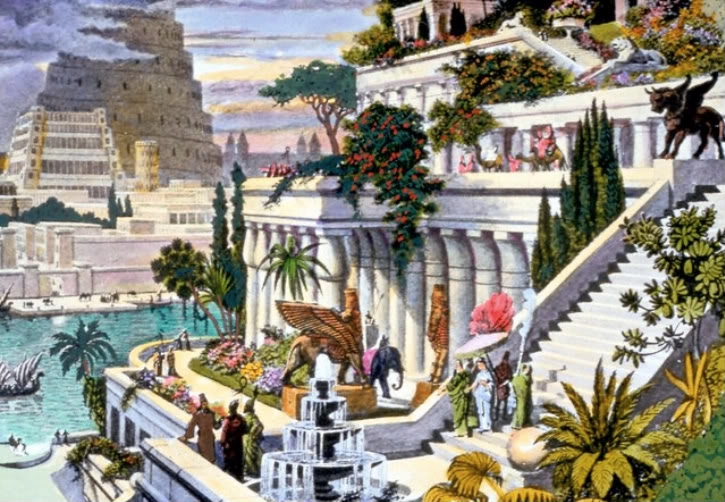

Even more famous than Sennacherib’s gardens at Nineveh are the legendary Hanging Gardens of Babylon. These are described in a handful of relatively late Graeco-Roman sources, which inspired some of the most spectacular reconstructions, such as the one you see here.

Hanging Gardens of Babylon. 19th century illustration.

Yet no Babylonian text mentions such a structure, nor has archaeology uncovered any trace of it. What we can say with confidence is that Babylon certainly had gardens, perhaps even elevated ones on rooftops. But the notion of a single, monumental ‘Hanging Garden’ is a later invention, an enduring myth that nonetheless reflects how deeply gardens were woven into Mesopotamian culture and imagination.

Paradise in the Persian Empire

When the Persians conquered Mesopotamia and much of the wider Middle East, they inherited and expanded the tradition of building grand gardens and parks. Known as parai-daeza (meaning ‘walled enclosure’, the origin of our word paradise) these spaces gathered plants, trees, and animals from across the empire. They served not only as displays of wealth and abundance, but also as royal hunting grounds reserved for the nobility. Found in every major city, these gardens stood as living symbols of the vast reach and universal claims of Persian kingship.

The Garden of Eden

It was during the Persian period that the story of the Garden of Eden was first written down. The Jews, living in exile in Babylon and mourning the loss of their homeland, shaped a myth to explain the human condition—defined by labor, pain in childbirth, and the inevitability of death. To do so, they imagined a blissful primordial land, cast in the form of a parai-daeza, a walled garden.

The story is one of the most famous in the Bible. God creates a garden for Adam and Eve, where nothing is lacking. They are free to eat from any tree except one: the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil. Of this tree, God warns, the day they eat from it they will surely die. Enter the serpent: not yet Satan, but a trickster figure. It tempts Eve, insisting that eating the fruit will not bring death, but instead open her eyes and make her and Adam ‘like the gods’.

Driven by curiosity, or perhaps by hubris, Eve takes the fruit and shares it with Adam. Their eyes are opened. They now know good and evil. But this new knowledge comes at a price. As in so many myths, the gods cannot allow mortals to rise to their level. To prevent Adam and Eve from also eating from the Tree of Life and becoming immortal, God banishes them from the Garden.

The meaning of the story, in its original setting, is straightforward. It is a cautionary tale about the dangers of human pride, while also explaining the harsh realities of life: why we must work, why women endure pain in childbirth, and why all humans must face death. But that was only the beginning of its journey. In the centuries that followed, the meaning of Eden would be radically transformed, shaping not just theology, but the way entire civilizations imagined the human condition.

More on that in a later blog…